The Forgotten History of Walden Pond

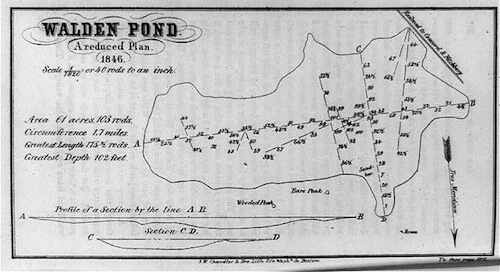

Each year, half a million people visit Henry David Thoreau’s cabin at Walden Pond in Concord, Massachusetts. Thoreau, one of the most prolific authors of his time and a leading transcendentalist, escaped to Walden Pond to live a simpler life. In “Walden” he writes:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.

However, Thoreau wasn’t the only one escaping to the woods of Concord. For many of Concord’s enslaved residents and marginalized groups, the woods offered a place of solace and a symbol of freedom. Though Henry David Thoreau is one of the most quoted authors, the people he writes about are frequently forgotten. The history of the other residents who lived near Walden Pond in the 1800s is profound, and their legacy is still intact today.

Concord, located northwest of Boston, is most notable for its associations with freedom. In 1775, the town of Concord led the first organized armed resistance against the British rule. After Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride, the Minutemen engaged British troops in the Battle of Concord, launching the American Revolutionary War. After the war, in the nineteenth century, the town experienced a literary and intellectual revolution. Authors like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau moved to Concord and became central figures to the transcendentalist movement. Transcendentalists promoted individual freedom, self-determination, and resistance to authority in their works.

During the 1850s, Concord was also a stop on the Underground Railroad for slaves escaping to freedom. In the Abolitionists Neighborhood, there were many houses that welcomed slaves and fugitive travelers. The Wayside, for instance, was a house that belonged to the Alcott family, including Louisa May Alcott, author of Little Women. This house sheltered two self-emancipated slaves who were escaping to Canada for freedom and taught Louisa May Alcott about slavery, which would later influence her writings. The Thoreau-Alcott House was also instrumental in aiding slaves escaping to freedom. Henry David Thoreau, who moved there with his family in 1850, wrote in his journal about lodging a self-emancipated slave named Henry Williams and putting him on a train north to Canada. The Concord Depot also allowed the Underground Railroad to connect to northern towns.

It may be surprising that Concord itself was also a slave town in the eighteenth century. In Black Walden: Slavery and Its Aftermath in Concord, Massachusetts, Elise Lemire, professor of literature at Purchase College, attempts to preserve the legacy of the enslaved people in Concord. According to her research, in the eighteenth century, several of Concord’s wealthier residents were slave owners. For many people in the town, owning slaves was a sort of status symbol, and slave labor allowed professionals like doctors, ministers, and landowners to dedicate more time to their work. Though slaves only made up around two to three percent of the population, Lemire points out that there were nearly twice as many slaves than scholars had previously noted. In addition, the free people of the town helped maintain the institution of slavery by questioning suspected runaway slaves and refusing to free them. During the American Revolution, the town’s slaves were able to leverage political tensions by exposing their masters to the British as patriots. Once it became clear that the slaves would make themselves a liability to their masters, they were abandoned.

However, once they were no longer under the control of their masters, the former slaves were only permitted to live in the most remote and infertile places, namely the woods surrounding Walden Pond. Thoreau’s cabin was situated in a village with 15 former slaves, whose stories contributed to his anti-slavery sentiments. In his journal, he wrote

Talk about slavery! It is not the peculiar institution of the South. It exists wherever men are bought and sold, wherever a man allows himself to be made a mere thing or a tool, and surrenders his inalienable rights of reason and conscience. Indeed, this slavery is more complete than that which enslaves the body alone.

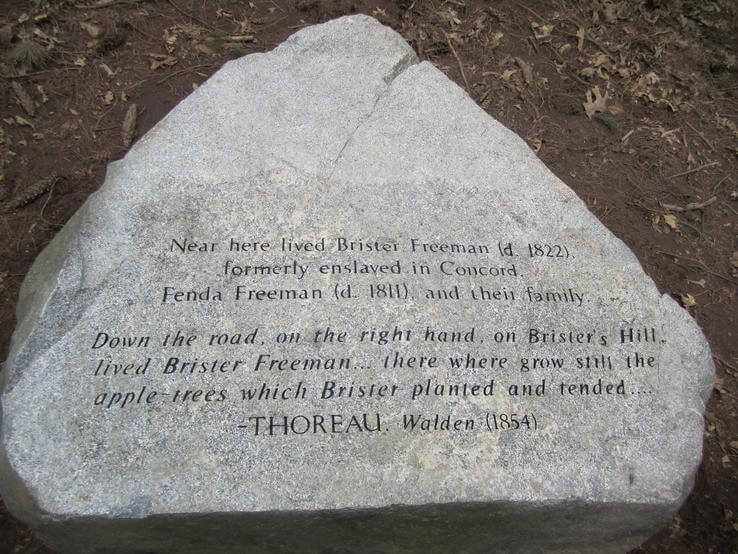

Hoping to preserve the legacy of Concord’s former slaves, Thoreau wrote about them in “Walden.” In particular, he writes about three formerly enslaved people: Brister Freeman, Cato Ingraham, and Zilpah White.

Thoreau wrote particularly fondly about Brister Freeman, who was given as a slave to Dr. John Cuming when he was nine years old as a wedding present. Freeman was enslaved for twenty-five years, managing the Cuming estate where he acquired farming skills and learned about local politics. After fighting in the Revolutionary War, he advocated for his freedom and took his rather apt surname. With the money that he had, he purchased the “old field” in Walden Woods and set up a two-family household with another African American Revolutionary War soldier. He had three children with his wife, Fenda Freeman, who was known to tell fortunes. Though he was frequently harassed by local officials and had his land taken away, he continued to live on what he considered his land. As a result, Thoreau describes him as a rather heroic figure, comparing him to the great Roman general, Scipio Africanus, and the townspeople began calling what was once known as Stratton’s Hill, Brister’s Hill. Today, the site of his home is marked on Thoreau’s path.

Another enslaved individual that Thoreau wrote about was Cato Ingraham. His master, a local squire named Duncan Ingraham, planned to move to Medford, Massachusetts in 1795. Cato, hoping to stay behind to marry a servant named Phyllis, pleaded to stay in Concord. Duncan allowed him to stay only if he severed all ties with him and sought no further financial assistance. Cato traded the financial security for his future bride, though Duncan agreed to purchase him a house in Walden Woods for his new family. He hosted several boarders to help with his expenses, but eventually died of malnutrition. The site of his home is also marked near Walden Pond.

Finally, Thoreau also wrote about a formerly enslaved woman named Zilpah White. He wrote that “she led a hard life, and somewhat inhumane.” Zilpah lived in a one-room house and managed to survive alone for 40 years. People often spoke about her as a witch, because she spun linen, had a garden, and made “the Walden Woods ring with her shrill singing.” Her house was both her residence and her barn, so she lived with dogs, cats, and chickens. Though Zilpah was also harassed by local town officials, it is remarkable that she was able to live alone to the age of 82.

Though the village near Walden Pond was not able to survive due to several external factors like access to food and hospitable land, Walden Pond State Reservation remains an important African-American heritage site, memorialized by the works of Henry David Thoreau.