AMC Backcountry Caretaker Program Turns 50

Perched high in the rugged boreal forest in New Hampshire’s Franconia Notch, Liberty Springs Tentsite is a haven for backpackers seeking a place to bed down for the night and rest their aching muscles after a long day of hiking. Located directly off the Appalachian Trail, the tentsite turns into a bustling Grand Central station in the summer, full of thru-hikers, camp and college groups, and first-time backpackers on trips lasting from a weekend to several months. An Appalachian Mountain Club caretaker lives and works at the campsite from Memorial Day through Columbus Day where they teach campers about backpacking etiquette, maintain the composting outhouse, and work on the trails. Although caretakers spend most of their time working by themselves, their interactions with their guests have defined their role in the backcountry for 50 years. In the late 1960s, a backpacking boom in the White Mountains created problems AMC’s Trails Department had never dealt with before.

Advancements in outdoor gear and an increase of expendable income and vacation time afforded people with more opportunities to camp with family and friends. At the time, AMC’s trail crew, with help from the New Hampshire Chapter, maintained seventeen shelters between Kinsman Notch and Andover, Maine. The influx of visitors strained the department’s ability to provide adequate services at the campsites, including repairing structures, disposing of litter, and offering wood for designated fire pits. Furthermore, backpackers were cutting new campsites in the forest, which resulted in more waste and ecological damage.

In the midst of this predicament, trail crew members Ed Spencer and Mark Dannenhaur wrote a report in 1969 titled “The A.M.C. Shelters—What Future?,” which recommended action items that AMC’s leadership and Trails Department should take to quash the rising backcountry issues. In the report, the authors noted, “It is ironic that while the AMC prides itself as being at the forefront of the conservation struggle, its own facilities are destroying their natural surroundings.” They go on to state, “The White Mountains wouldn’t be able to maintain even their semi-wilderness character . . . unless there is careful planning on the part of the Forest Service and the AMC.” The report spurred AMC into action and in the summer of 1970, the Trails Department embarked on new era of backcountry campsite management.

The department chose Liberty Springs as its pilot campsite for many of the improvements, as the popular destination “exhibit[ed] the greatest overall destruction, yet offer[ed] the greatest possibility of a meaningful change.” Upgrades included replacing the campsite’s aging shelter with tent platforms to disperse parties at separate sites, thus limiting the impact on the environment and providing a more primitive camping experience. To reduce waste, trash was burned and non-burnables were crushed and flown or packed out. In addition to flying refuse out of the backcountry by helicopter, the department also refurbished the outhouses so waste could be flown out in metal containers instead of digging new pits into the mountainous ledge every time one filled.

The most notable change the Trails Department implemented was, for the first time in AMC’s history, staffing a backcountry campsite with a full-time caretaker. As part of its pilot project, the department wanted to test whether an ongoing presence at Liberty Springs would minimize littering and tree cut-ting through onsite outreach and education. In their report, Spencer and Dannenhaur advised AMC leadership, “If one is not present at the major new facilities, all the precautions and developments which we have proposed will improve nothing for the ignorance of a few hikers will start each area on the way to degeneration.”

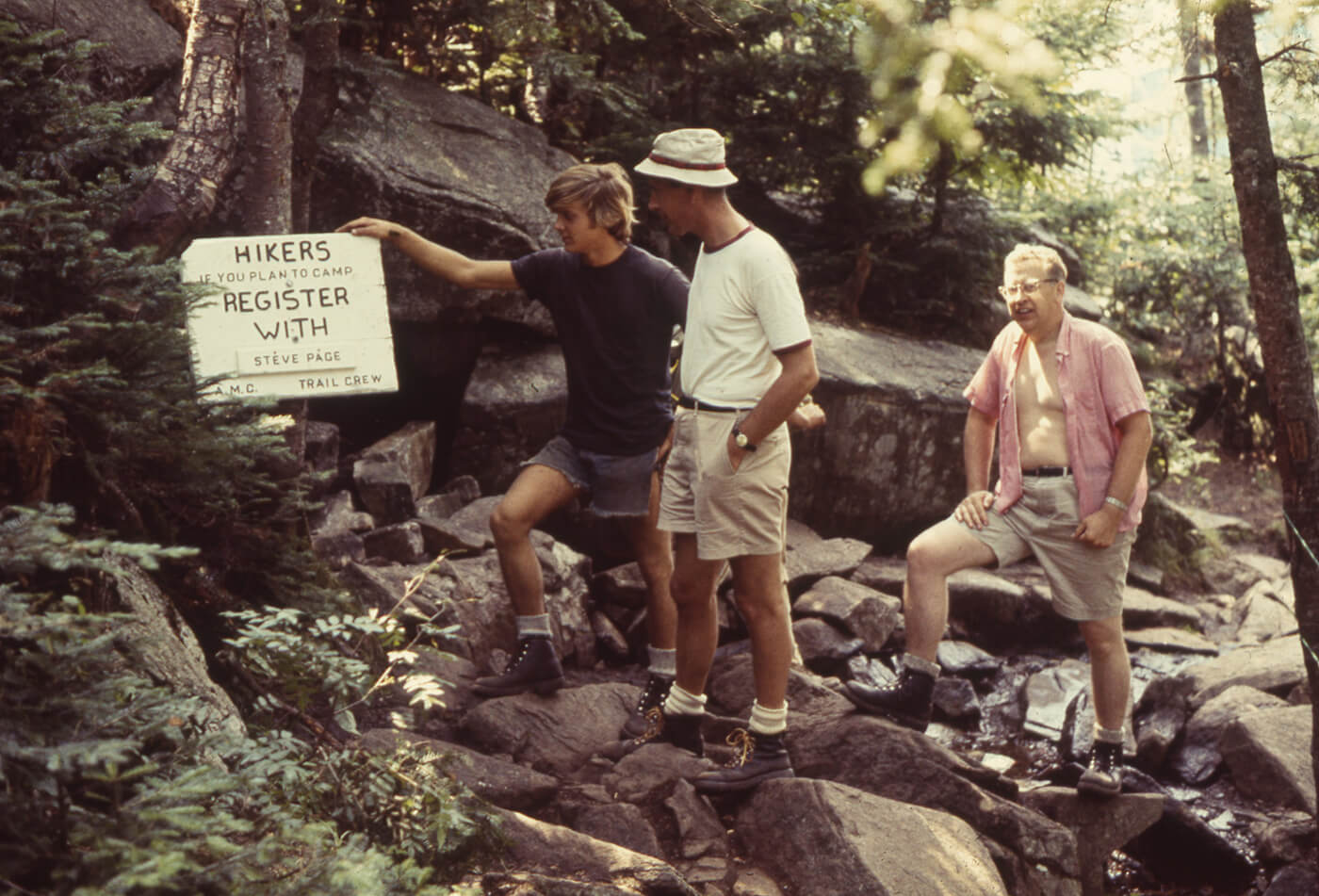

In a story about the pilot program featured in Appalachia (December 1970), trail crew member Steve Page wrote that in addition to working on trails, planting trees, and assigning tentsites, the caretaker’s primary job is education. “Very few people who hike in the backcountry consciously seek to destroy the environment, but often, carelessly and thoughtlessly, they do,” he wrote, adding that the caretaker’s “function is to show hikers how to enjoy the mountains without destroying them.” Page, a Pennsylvania native who started rock climbing with his local AMC chapter in 1966, was the first care-taker at Liberty Springs Tentsite. He recalls that not every backpacker was fond of the caretaker pilot, but by teaching his guests about his role in car-ing for that place, many eventually came around to accept the concept. By 1972, the department had hired caretakers to work at four popular campsites: Guyot, Ethan Pond, Speck Pond, and the newly built Garfield Ridge. Progress was being made and AMC’s leadership was taking note. In AMC’s 1972 annual report, Trails Supervisor Bob Proudman lauded the program by saying “The trail crew has risen to the task of managing primitive facilities under the pressure of increases in public use. In doing so, they have set an example of the true possibilities that the manager may engage in.”

The Formative Years

What began as an experiment in 1970 evolved, by 1996, into a stand-alone program consisting of a full-time manager and a seasonal field coordinator, group outreach coordinator, and twelve caretakers overseeing fourteen campsites. In the 1990s, Hawk Metheny, shelters field coordinator and then supervisor, bolstered the campsites with new infrastructure. He and his staff converted the last remaining pit privies to batch–bin composting systems. They created “beyond the bin” liquid separators for all the sites. Metheny was named the backcountry management specialist in 1999. He remained in that position until 2010, when he left AMC to work for the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. By 2011, many of the aging shelters were in need of repair.

Sally Manikian, campsite program and conservation manager from 2010 to 2016, presided over the restoration of Gentian Pond and Ethan Pond shelters and the replacement of Eliza Brook and Garfield Ridge shelters. As overnight numbers rose steadily over the years at the campsites, the program developed innovative management practices to prevent any unnecessary dam-age to the campsites and the environment.

The Overflows Are Overflowing

Today, the White Mountain National Forest is experiencing another surge of hikers and backpackers. In 2018, the campsites registered a record 18,500 overnight stays at sites staffed by caretakers. The next year the number stayed high, with 18,300 overnights. Had the COVID-19 pandemic not occurred, Backcountry Campsite Manager Joe Roman was anticipating a record-breaking year in 2020. Roman has watched numbers grow from about 800 visitors every year since 2012 and worries that the campsites are at the point of being unsustainable. Caretakers follow the adage of never turning away a guest from staying for the guest’s safety and to consolidate camping impacts in one location. But now, Roman notes, that policy is hampering their ability to provide safe and enjoyable services. On busy weekends, caretakers are sometimes left with no other space for guests to camp than in overflow spots and even undesignated areas. “We have a lot of anecdotal evidence from surveys,” Roman says, “that reveals that while visitor numbers are rising, the visitor experience is dropping.” The more people caretakers try to accommodate, the greater the impact on the campsites and the campers’ experience (and likelihood that they will want to go back). “Our campsites are for all ability levels, but especially beginner backpackers, so we want their first experience to be good,” Roman says. “We want people to come back to the woods, and we want to be able to cater to them. If that’s going to happen with the way numbers are rising, we have to change in some way.”

On December 10, 2020, Roman and Metheny hosted a virtual reunion to celebrate the caretaker program’s 50th anniversary, and 60 past and present caretakers attended. Tapping the knowledge and experience the group possessed, Roman and Metheny led a discussion about the future of the program and the ways it could address the visitor use issues at the campsites. Everyone agreed that although there isn’t a clear answer about what to do next, caretakers have and will always be up to the task of setting a sustainable course for the next generation. Joan Chevalier, the first woman caretaker at Guyot in 1976 and one of the first women to join the trail crew in 1977, recalled her caretaking experience influenced the rest of her life. After leaving AMC, Chevalier’s work took her all over the world. She noted that when she returns to hike in the Whites, she can see more signs of use on the trails but believes it would be worse without caretakers. “It’s great to see that the program has grown as the use has grown because the Whites are such a fragile place,” she said. “Fifty years later, I’m really excited to see that the program is so robust and playing such an important role in protecting the Whites. It strikes me that the caretaker program is more important than ever.”