Do Cell Phones Belong in the Mountains?

A 24-Mile Journey with a 1-Year-Old Suggests a Quieter Mountain Way

This story was originally published in the Summer/Fall 2022 issue of Appalachia Journal.

My son was asleep on my back, head craned sideways as he slouched in a child carrier, oblivious to the marathon journey in front of us. We were hiking up the Garfield Trail in the predawn darkness of August 2021, my headlamp lighting the rocky path, and his heavy breathing exchanging a rhythm with my crunching footsteps.

An imagined news headline flashed across my eyes: “Father deemed grossly negligent for bringing 1-year-old on 24-mile hike across New Hampshire’s White Mountains without cell phone.”

I pushed the thought out of my mind and tried to focus on the trail. My heart raced with excitement and trepidation as my son Mansfield and I plodded toward Mount Garfield, to be followed by Galehead and then Owl’s Head, our 48th and final 4,000-footer together. Today’s 24-mile hike would tick off these last three summits on our list of New Hampshire’s tallest mountains. And Manny, I was told, could very well become one of the youngest people to ever complete all of New Hampshire’s 4,000-footers.

I couldn’t shake the nagging feeling that I was doing something wrong—that each step I took into the Pemigewasset Wilderness was a misstep. My pack weighed about 50 pounds from my son, water, food, diapers, and extra clothing. One thing I didn’t carry, however, was any kind of technology that would enable us to connect with the outside world. No phone. No GPS. No emergency beacon. Off-line and incommunicado, we were on our own. If I sprained an ankle, fell and hurt either of us, or got lost, we would be hours from the nearest trailhead and unable to call for help.

“What was he thinking?!” I imagined critics saying. “What cavalier, reckless, horrible parenting!”

My legs already ached. The previous day, we had hiked 23 miles over the summits of six other Pemigewasset peaks (the Twins, Zealand, and the three Bonds). My wife, Jenna, with our 3-month-old second child in tow, had picked us up at the Lincoln Woods trailhead, and we had all stayed at the Seven Dwarfs Motel in Twin Mountain. If you’ve ever tried to stay in a motel with two kids under 2 years old, you can understand why I’d slept only four hours.

Given that my tank was half-empty, did I have a parental responsibility to at least carry a cell phone now, despite all my qualms with the devilish device? That is, was I acting negligently in not carrying one in the mountains?

Wiring the Wild

For more than a decade, as a matter of principle, pride, and stubbornness, I have refused to own a cell phone. In 2009, years before I was first introduced to the White Mountains, I threw away my first and last phone after a torrid, four-year, love-hate affair with it. I’d slept with the device, heard phantom calls from it, and felt tethered to it as a social lifeline. It was the last thing I looked at before bed and the first thing I reached for in the morning. It was a source of joy when a friend called, misery when a boss checked in, angst when nobody called at all.

I was alarmed by my addiction to such a simple device and disturbed by research showing that the cell phone—and its role as a major conduit for social media—undermines people’s ability to focus, live in the moment, maintain eye contact . . . to be thoughtful humans, in many ways. So I threw it away. Living phoneless seemed like a way of maintaining some quiet in my life, ensuring that I would be off-line for at least part of my days. I’ve come to embrace this lifestyle. I even wrote a book about an area of America known as the National Radio Quiet Zone where cell service is outlawed and smartphones are restricted, which sounded like heaven to me. (The reality was more complicated, like many things.)

In general, I’ve never been a fan of modern means of “connecting” through cell phones or social media. I’ve never been on Facebook or Instagram, much less Snapchat or TikTok, because of a Thoreauvian wariness of these supposed advancements in communication. (“We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas, but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate,” Thoreau wrote in Walden, in a line that presaged most of what’s on social media today.) When I bicycled across America in 2004, I opted against carrying a cell phone because I wanted to really be on my own. (Half the trip was solo.) That I wouldn’t always be able to call for help made the adventure epic, memorable, life-changing, and, well, adventurous.

I feel the same way about going into the mountains. A cell phone undermines the adventure and spirit of the backcountry for me. And I’ve found that I’m not alone in this conviction.

“A cell phone in your pocket erases maybe the most glorious part of being out there in the mountains,” Laura Waterman, a prolific hiker and writer who is something of a godmother to the Northeast’s outdoors community, told me. “You’re erasing any trace of self-reliance.”

Whether to bring a phone into the backcountry is a question of ethics, says Waterman. She’d know: She literally wrote the book Backwoods Ethics (Countryman Press) with her late husband, Guy. First published in 1979*, it made an early case for low-impact hiking, climbing, and camping as a way of protecting nature and experiencing a sense of the wild. Cell phones didn’t exist back then. But four decades on, Waterman believes the device has caused the “biggest change” in humans’ relationship with nature, enabling us to “carry our everyday lives with us when we’re out in the wild,” as she wrote in the new introduction to the 2016 edition. The technology prevents us from escaping our everyday world and creates a digital barrier to engaging with the outside.

That said, Waterman does own a cell phone. An old Tracfone is stashed in her car in case of emergency. It never leaves the glovebox, and it certainly never goes on hikes, she said.

Waterman is hardly alone in opposing cell phones in the backcountry. The nonprofit watchdog Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER) has for years advocated to keep wild places cell-free and opposed the National Park Service’s plans to install cell towers across America’s national parks. “A national park is supposed to facilitate the public’s ability to enjoy the natural world and be able to escape the electronic tendrils of civilization,” PEER’s executive director told Sierra magazine in 2020. “To commune with nature. To unplug. The Park Service is doing the very opposite. It’s wiring the wilderness.”

After I spoke with Waterman, she snail-mailed me an excerpt from a new book, The Appalachian Trail: A Biography (Mariner Books, 2021), by Philip D’Anieri. Its final chapter addresses “the Internet-ization of the AT,” with hikers stopping in towns to recharge battery packs and download shows to be watched in huts and shelters. Smartphones allow hikers to bring the world onto the trail and the trail to the world, with some hikers livestreaming their 2,190-mile journey and turning what was once a personal sufferfest into a public performance.

John Marunowski, a U.S. Forest Service wilderness manager for the Pemigewasset Ranger District since 2004, said he noticed this internetization of the trail about a decade ago. All of a sudden, every thru-hiker seemed to be asking if they’d get cell service atop the next mountain.

“Part of me was disappointed,” Marunowski told me. “Is that what the experience has turned into?”

I have to wonder why so many people take cell phones onto trails, given the devices are widely reported to cause stress and anxiety. “It’s a matter of safety,” some hikers have told me. But digging into this topic, I’ve found that many search-and-rescue professionals believe that cell phones are unessential in the backcountry. They even say the device can be dangerous.

“A Big Mistake”

Five miles into our trek, Manny and I summited Mount Garfield, scrambling up the old fire tower foundation just after sunrise. The wind chafed our cheeks and made our noses runny, but otherwise the weather was perfect: blue sky, wispy valley fog, and a 360-degree view of peaks and ridges soaring thousands of feet above the forest. I felt no itch to check social media or post a selfie, no desire to call my wife or check if she’d messaged. Nor was there a cell tower in sight to blemish the view.

We hiked three miles across Garfield Ridge to Galehead Hut, where I signed our names in the register. Manny relished the opportunity to walk around and explore, stretching his legs. A hut crew member was surprised to see such a tiny creature in the hut, and she welcomed him to drink all the apple juice he wanted. She added that, earlier that summer, she’d seen a woman carrying her 3-year-old on a one-day circuit of the entire 32-mile Pemi Loop—meaning my endeavor was by no means at the edge of insanity.

From the hut it was a quick jaunt up Galehead Mountain before we descended into the isolated valley around Owl’s Head, where at some spots we would be about twelve miles from the nearest road. Without a cell phone, I was potentially cut off from a primary means of rescue but, at the same time, I had embraced the ethics of self-reliance and enhanced our adventure. Isn’t adventure why we go into the mountains?

In a 1995 essay for Appalachia titled “Let ’em Die” (vol. 50 no. 4, pages 42–55), the Canadian mountaineer Robert Kruszyna argued against the idea of search and rescue because it “robs climbing of its sense of adventure, which is probably the only meaningful justification for an otherwise useless activity.” That extreme position may be unpalatable to many people. But I appreciate the sentiment. Being self-reliant is part and parcel to an adventure. And one way to double-down on self-sufficiency is to ditch the cell phone.

Despite all of these ideals, is Kruszyna’s “sense of adventure” a justifiable trade-off for not carrying a relatively lightweight device that could potentially save lives? Setting aside backcountry ethics, was I failing to take a simple safety precaution by not bringing any emergency communications technology? That is, is the cell phone an essential part of the hiker’s toolkit?

I brought that question to Lieutenant Jim Kneeland of New Hampshire Fish and Game. He heads NHFG’s sixteen-member Advanced Search and Rescue Team, which handles rescues throughout the White Mountains. If anything happened to me, Kneeland would likely have coordinated the response as well as determined whether I would be billed for the rescue. A state law allows NHFG to bill hikers judged to have acted negligently, which can mean they didn’t carry basic items like a map or headlamp.

I asked Kneeland, Would a hiker be deemed negligent for not carrying a cell phone? No, he said. Neither a cell phone nor any kind of electronic communications device is on the hikeSafe list of ten essentials, meaning they are not required or necessarily recommended. “And I don’t think it will ever be there,” Kneeland added.

He said the cell phone is an unreliable tool. “They’re fine to carry with you,” he said, “but to rely on it as one of your essentials is a big mistake.”

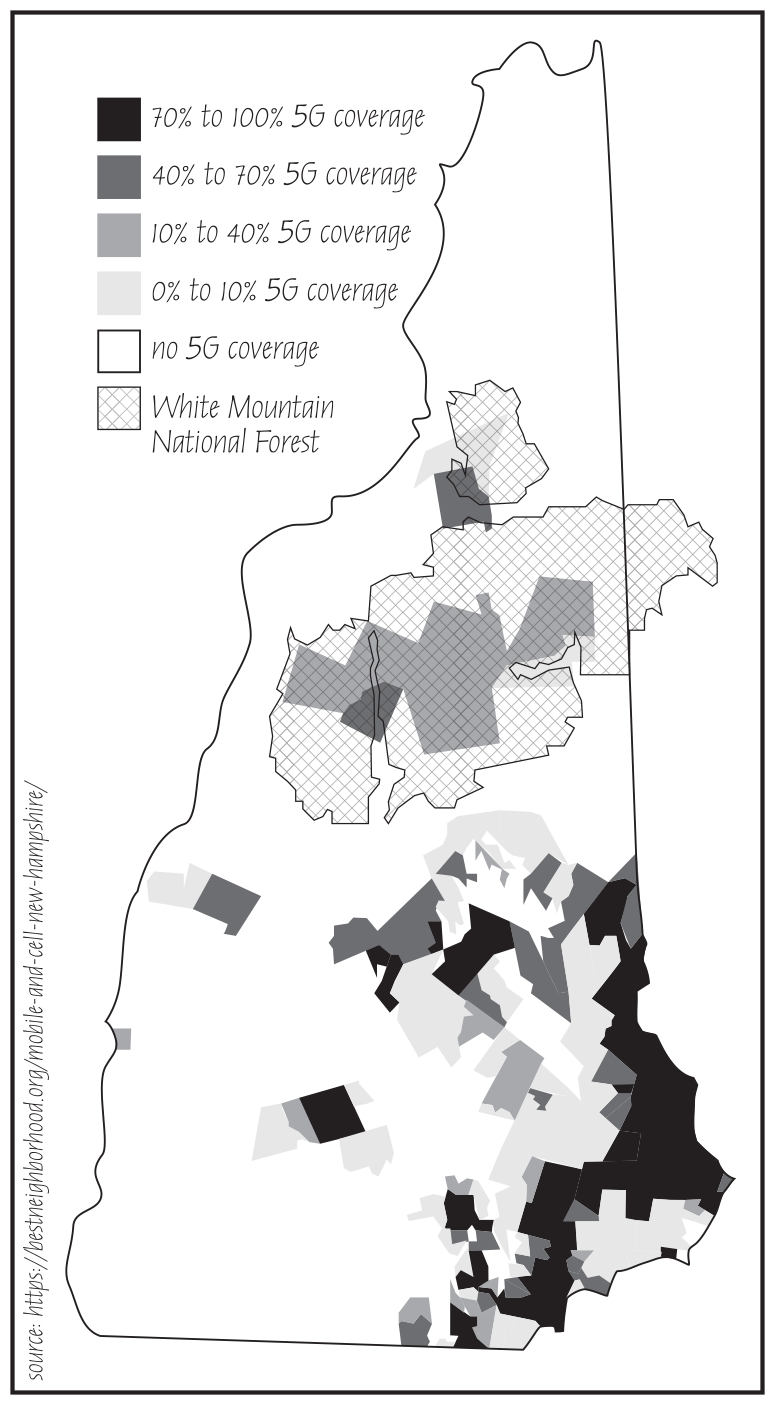

For one thing, cell service is patchy in the White Mountains and variable with many factors, including terrain and weather. Kneeland estimated that less than half of the Pemigewasset Wilderness has cell service, which can come as a surprise to many hikers. After all, we’re encouraged to think our devices will always work. “Can you hear me now?” the man asks in the Verizon commercial, and he always gets a response. We’re expected to be always online, and this culture of constant connectivity casts a shadow over the mountains, even if the mountains aren’t always connected.

But where there is cell service, phones have made the backcountry safer, right?

There’s evidence to the contrary. According to a 2000 report from the USFS, cell phones and other emergency communications devices increase hiker confidence and make them less willing to retreat in the face of danger. Cell phones also lead self-identified risk-takers in the backcountry to put themselves in more precarious situations, according to a 2012 study from researchers at Humboldt State University in California. This has become a well-accepted idea. When Oregon tried to pass a bill that would require climbers to carry an electronic signaling device above 10,000 feet, the initiative failed because search-and-rescue teams feared it would embolden unqualified climbers, according to a 2015 article in Sierra titled “The Danger of a Life-Saving Device.”

SAR officials in New Hampshire have expressed similar reservations about cell phones. “I think there are people who take more of a risk thinking they can always make a call or even use their cell phone as a light in the night,” Joe Roman, the Appalachian Mountain Club’s SAR coordinator, told me. A representative from NHFG echoed that sentiment way back in 1997, telling Sandy Stott in Appalachia: “Hikers who go out with cell phones seem to overextend themselves; they go one or two steps farther than they should because they have a false sense of security” (“The Celling of the Backcountry,” vol. 60 no. 4, pages 48–59).

Roman does believe cell phones “have saved lives” because they enabled hikers to call for help and provided navigational technology, and I was told that all SAR personnel are required to carry cell phones and other emergency locator technology. But it’s unclear if cell phones have reduced overall deaths. Since joining NHFG in 1992, Kneeland has not noticed a decline in hiker deaths per capita, which suggests that cell phones have not made the mountains safer.

To put it another way: Would deaths spike if cell phones disappeared? “I feel people would self-rescue more, find their way out, crawl out,” said Marunowski of the USFS. “I wouldn’t be more worried.”

Kneeland said he’d never criticized a hiker for not carrying a cell phone. In fact, many times he’d wished hikers hadn’t carried cell phones at all. The device has led to a rash of nuisance calls, particularly during the shortening days of autumn when hikers are “trapped by darkness.” Almost every night in fall is a triage for Kneeland, who often finds himself hunched over a computer, toggling between maps, handling call after call from hikers who carried no map or lamp.

“When something starts going wrong, hikers are quick to call 911 and request assistance,” said Kneeland. “I’m not opposed to giving that assistance, but a lot of times they probably could have worked themselves out of their mess by carrying appropriate equipment such as a map or headlamp or something like that.”

Sometimes Kneeland will tell a benighted hiker to wait for another person to come down the trail with a headlamp, or to enjoy a night in the woods and self-rescue when the sun rises. That rarely goes over well. “They’re going to call me every five minutes,” he said. “Quite often they keep you up half the night, so you might as well go get them and be done with it so you can go back to bed.”

Everyone expects Kneeland’s immediate attention, as we’ve all come to expect instant service in all forms: an Amazon delivery, a Google search result, a 911 response. Nobody is willing to wait patiently for the aid of a Good Samaritan or the morning sunlight. Sandy Stott, the Accidents editor of this journal, even heard of a group that called 911 asking for two things: directions out of Tuckerman Ravine and a delivery of pizza.

A Prayer

Under the full force of August’s midday sun, the relentless, mile-long talus field up Owl’s Head felt heart attack–inducing—especially with a whimpering child on my back. Dirt and rocks shifted underfoot as if I was in beach sand. An unofficial trail, the path felt like one of the more precarious in the White Mountains, where a slip could easily turn serious. (Two years earlier, in fact, a man reportedly had suffered a “medical emergency” here and died.)

We finally topped out on the forested summit dome. After another quarter-mile hike through the bush, we stopped at a trail-ending cairn, where I set Manny down. I swallowed some ibuprofen. Manny trotted about and pooped in his diaper. This would be his twentieth and final diaper change above 4,000 feet, as I’d been keeping tally since we started this whole endeavor more than a year earlier.

Coming down Owl’s Head, we crossed paths with a brawny, shirtless man trudging uphill with a four-foot-long log propped over his shoulder. He said the log weighed 25 pounds and that he was training for a strongman competition. We then passed a father and his teenaged son, and the father seemed to eye me judgmentally. I jittered downhill and skirted around him. The ibuprofen had put a pep in my step.

“It’s a good thing you’re not alone,” the father said.

“Right, I’ve got my 1-year-old with me!” I responded.

“You know that’s not what I mean,” he said with a glare. “I’ll say a prayer for you.”

The man’s over-serious religiosity grated on me, as did the fact that he felt I needed somebody to watch over me. It seemed to underscore something about the desire many people have to remain connected with an all-powerful overseer, be it God overhead or AT&T in our pocket. We’re uncomfortable to the point of being existentially terrified at the idea of being alone. Going into the mountains used to force everybody to get comfortable with that aloneness. It was baked into the adventure. Now it’s an option that more and more people opt out of.

I would later recount my trip to Ty Gagne, another father who has brought his kids into the White Mountains many times. He’s also the author of two of the most well-read books about accidents in the White Mountains, so I wanted his assessment of my decision to do a 24-mile wilderness hike with a 1-year-old and without any communications technology. Gagne’s first book, Where You’ll Find Me, recounted the 2015 death of Kate Matrosova, whose rescue was delayed when her personal locator beacon emitted a series of conflicting coordinates that initially sent rescuers in the wrong direction; technology failed her. His second book, The Last Traverse, told the story of two hikers stranded on Franconia Ridge in February 2008 with no communications device; technology might have saved them.

Neither of those books is a lesson about technology being a menace or messiah, Gagne told me. The lesson from both is how our own behaviors and emotions fuel our decisions. And he found it a reasonable emotion to want to disconnect when in the mountains.

“I miss the simplicity that existed before this kind of distraction tool that’s become an extension of our bodies,” Gagne said. So far as the wisdom of bringing a 1-year-old deep into the woods, Gagne reserved judgment. “I can’t sit here and criticize what you did because people have been hiking in the backcountry without technology longer than they haven’t.”

Phone-Free Zones

As part of my research, I reviewed the past decade of Accidents reports from this journal to see how cell phones have played into rescues. If essential, wouldn’t cell phones be celebrated as lifesaving devices?

I found phones often mentioned in a negative light. A winter hiker took her smartphone up Mount Monroe, then took so many photos that her battery died, and with it her map. There was the teenaged trio who embarked in late afternoon on a nine-mile hike with total equipment of “a half-bottle of vitamin water and three cell phones”; they spent a rainy, hungry night in the woods when they lost cell service, and their way. There were numerous incidents of hikers calling for help when they could have problem-solved their way out. Once, more than 30 rescuers responded to a hiker with an injured ankle who, ultimately, was able to walk down. The device caters to panic. In another incident, a hiker called 911 for another group, which later told the 911 responder that it never wanted help.

“Clearly, there is a lot less ‘muddling one’s way out,’ and a lot more pressing buttons for help,” Stott wrote in one Accidents column. In his 2019 book Critical Hours (University Press of New England), Stott recounted the egregious case of a man who called for help from Mount Adams because he’d injured his leg. A SAR crew carried the man down four miles of steep terrain. At the parking lot, the injured hiker rose from the litter, stood on both feet, and announced he was OK then. In another recent case, a Dartmouth College student got lost within 1.5 miles of Moosilauke Ravine Lodge. He’d been looking at his phone as he hiked; when he looked up, he couldn’t spot the trail. He was found two days later, shoeless and hypothermic.

“Trading the actual world for the screened one invites collision with objects such as trees, stones, or mailboxes,” Stott commented in his Accidents report. “But the loss of awareness of one’s real world is deeper than that. The screen life becomes the familiar one; the real life becomes surpassingly strange.” Stott’s warning resonated for me. Were I to hike with a smartphone, I worry that I’d become overly obsessed with the tiny screen, checking email and whatever else from the trail, endangering myself and Manny because I’d lose focus of my surroundings.

In a phone interview, Stott told me I wasn’t wrong to detect his exasperation with cell phones. “A lot of times, at the first sign of difficulty, people get on their phones in no small measure because that’s the habit that seems to be reinforced and reinforced and reinforced, and so it’s gotten stronger,” he said.

Stott has watched this trend play out over a quarter-century. In that prescient 1997 article “The Celling of the Backcountry,” he described a weekend trek up Mount Jefferson when he found that half of all hikers carried cell phones; one man even claimed to have “done deals from all over these mountains,” meaning business transactions. Cell phones were already ubiquitous—so much so that the USFS was discouraging the use of phones in the woods and campgrounds because they intruded on “the backcountry experience,” there was a “consensus” among SAR officials that “cell phone use in the mountains was ‘getting out of hand’” with nuisance calls, and in 1995 the Randolph Mountain Club had instituted a no-phones rule at its shelters.

RMC still prohibits cell phone use at its four backcountry shelters. Each shelter has a sign that reads, “Cell Phone Free Zone,” which is enforced by the club’s caretakers and field supervisors. The nonprofit’s camps chair, Carl Herz, told me that enforcement is a kind of mental jujitsu or Jedi mind trick—an effort to convince visitors that the rule is in their best interest, and that the sound of the wind is preferable to that of a TikTok video.

“Nobody wants to run into a sheriff,” Herz said. “It’s more about trying to facilitate an environment where they don’t want to look at their phone. You might need to gently remind people about the policy and just say, ‘Hey, we ask that people use those outside. We try to keep it pixel-free indoors. I know you need to let your wife know you’re OK, but step outside and then come back in and eat by the lantern.’”

The Gray Knob caretaker for seven seasons from 2015 to 2018, Herz said he could count on his hands the number of times he had to crack down on phones. But there was one memorable incident. In the fall of 2015, a group of eight hikers arrived around 9 p.m. and began complaining about the spotty cell service. Herz casually mentioned that cell phones weren’t allowed inside but added that Crag Camp, a half-mile away, had excellent reception. Without any prodding, the group packed up and hiked through the dark to Crag, such was their desire to get online.

For Herz, it was a small victory to get phones away from the others at Gray Knob. To me, it sounded like a desecration of the sanctity of Crag Camp, like peeing in the church baptismal when nobody’s looking. But the reality was that it was impossible for Herz to be an all-seeing enforcer at all four of RMC’s shelters, so he had to choose his battles.

In contrast with RMC, the Appalachian Mountain Club has no regulations against phones at its two lodges, eight huts, and numerous backcountry shelters—which see tens of thousands more people every year than RMC’s 1,200 annual overnighters. Although cell service is spotty at Joe Dodge Lodge and the Highland Center, both facilities have strong Wi-Fi. In fact, the last time I stayed at Joe Dodge—the night before Manny and I completed a one-day, 20-mile Moriah-Carter-Wildcat traverse in June 2021—my cousin streamed a National Basketball Association Finals game on his smartphone late into the evening from his nearby bunkbed. (I confess I wanted to be kept updated on the score.)

Half of AMC’s campsites have cell service, according to Joe Roman, who along with being the organization’s SAR coordinator is also its campsite program and conservation manager. Phones usually aren’t an issue, he said. But there are cell phone–related annoyances, such as when AllTrails lists the wrong price for campsites and hikers show up expecting a lower fee—which might be the least of all problems with apps that are notoriously inaccurate and often downplay trails’ difficulty while focusing on their Instagramability.

At AMC’s huts, phone etiquette has improved as texting has become a more common, discreet means of communication, according to Huts Manager Bethany Taylor. She said AMC has even encouraged smartphone use by inviting hikers to participate in long-range phenology studies with such apps as iNaturalist.

“Using that app, folks can take pictures of flora and fauna along the way, which will help them identify the species, and the life stage of the plant, as well as provide the exact location of the plant,” said Taylor. “This is all collected and mapped out as a huge collaborative research project and shows more accurately when and where different species are budding, flowering, and fruiting.” A wealth of crowdsourced data is being collected.

“The trick, I think, that we’re all learning is to utilize smartphones as tools and to know when, where, and how they augment the experience of being in these special places,” Taylor added.

Somewhat ironically, RMC has also found cell phones to be useful. Since 2017, the club has stashed a smartphone at either Gray Knob or Crag Camp as a backup to its emergency radio and pager. The device is also used to process overnight fees—although, per club rules, the transaction occurs outside.

Tech Education

How do we keep cell phones in their appropriate place? One response is a “Katahdinesque” approach, as Stott calls it. Maine forbids the operation of radios, televisions, cassette players, and cell phones in Baxter State Park in an effort to follow former Governor Percival Baxter’s request that the land “forever be kept and remain in the natural wild state.” In the same vein, the park goes light on SAR because it takes away from the spirit of being in a wild place.

But even Baxter State Park is struggling to stay Katahdinesque. A previous park director told Stott that the no-phones policy had to be relaxed to attract young workers who wanted access to their devices. Visitors had also pushed against the regulation. In 2018, a park ranger told me they’d essentially given up on cell phone enforcement. At the summit of Katahdin that year, I found people taking selfies with their iPhones and making calls. A cell tower blinked on the horizon.

The White Mountains—being just a few hours from Boston and Montreal—are all the more accessible to millions of people, allowing the cell phone culture of the frontcountry to more easily pervade that New Hampshire backcountry. In 1997, USFS’s Rebecca Oreskes told Appalachia (“The Celling of the Backcountry,” page 55), it would be impossible to prohibit cell phones in wilderness areas. Herz of RMC also said there was no way to altogether ban phones in a public resource such as the White Mountains—not to mention in a state whose motto is Live Free or Die—so the best option is “education of reasonable use of tech.”

And one of the best education initiatives in the White Mountains, according to Lieutenant Kneeland, is the Trailhead Stewards Program. Started in 2014 by John Marunowski of the USFS, the program has grown—with financial assistance from the Waterman Fund, founded in memory of Guy Waterman—to include 150 volunteers who station from May to October at the five busiest trailheads in the White Mountains (Appalachia, Welch-Dickey, Falling Waters, Bridle Path, and Ammonoosuc Ravine). A single trailhead can see as many as 500 hikers in a morning.

“A lot of the stewards are playing triage,” Marunowski told me. “Somebody walks up to us and they’re about to hit the trail. We engage them and do a quick once-over of what they’re carrying. Are they prepared?”

The answer is often a resounding no, with overreliance on cell phones being a culprit. At Champney Brook trailhead one October weekend, a steward found that one in five hikers carried the recommended paper map; the majority relied on maps on their phones. Another time, the steward discovered hordes of Columbus Day hikers “unaware that they would need water, additional clothing, and that a paper map was preferable to a picture on the cell phone,” according to an Accidents report in this journal. (Compared with those hikers, Manny and I were almost comically overprepared with our paper map, two lights, and 11 pounds [5 liters] of water.)

It’s an uphill battle to influence people. About one in ten hikers will take a steward’s advice, be it to add layers or do a different hike, according to Marunowski. But even that is enough to help prevent incidents, according to Kneeland. His SAR team averages 200 missions a year, plus another 150 cases where the situation can be handled over the phone. The number of phoneonly responses jumped to 186 in 2020 when people flocked to the woods during the pandemic and the Trailhead Stewards Program was suspended.

When encountering unprepared hikers, trail stewards focus on the hike-Safe ten essentials. If hikers say their phones cover those essentials, it might spark a conversation about the superior reliability of a paper map and headlamp to a smartphone that’s hemorrhaging battery power every time you swipe right. If hikers display poor phone etiquette, such as playing music over a Bluetooth speaker connected to their smartphone, the stewards will speak up.

“We’d say, ‘People go into nature because they want to appreciate the sights and sounds of nature, and we would appreciate it if you kept that to yourself,’” Marunowski said.

Serendipity

From Owl’s Head, Manny and I still had nine miles between us and civilization. With the mental burden of 48 peaks behind me, I was soon skipping at a pace of four miles an hour. After a few miles, I veered onto an unmarked path that seemed to point in the general direction of home. I’d heard of an unofficial trail known as the Black Pond Bushwhack that could eliminate several water crossings and a mile or two. For a half hour, I anxiously wondered if I was on the correct bushwhack or a dead-end deer path. There was a sense of excitement and exploration in not being able to check my GPS location.

Soon we popped out at Black Pond, then converged with the Lincoln Woods Trail—we were home free. I looked down the long, tree-lined corridor of what was once a railroad bed and saw a familiar figure approaching. It was Jenna carrying our 3-month-old. (The previous year, Jenna had completed half of all the 4,000-footers with Manny and me, but our second child had sidelined her peakbagging endeavors.) The fact that we were reconnecting without relying on phones made our reunion even more serendipitous.

I’m not trying to argue that extreme hikes with kids are for everyone. But I am using my hike as a way of arguing against cell phones in the wilderness. If Manny and I could safely do such a trek, and without broad condemnation from respected voices in the Northeast’s mountain community, then I believe we all can start ditching our cell phones. It might help defend the spirit of the backcountry.

Because as surely as phones have infiltrated the mountains, won’t more invasive technology? It’s not hard to imagine hikers one day wearing Oculus headsets or another kind of virtual reality augmentation to enhance their experience. Think of the boon to safety. SAR officials could, in emergency situations, don their own VR headsets at home, and the officer could be virtually alongside the hiker, encouraging them down the mountain. “Virtual stewards” could station everywhere. Reality will increasingly blur with irreality, just as it’s happening every day with GPS replacing maps, Zoom replacing offices, social media replacing friendships. . . .

I go into the woods to escape that contrived world of fake plastic trees, which means leaving cell phones behind and embracing the rewards of going off-line.

* Backwoods Ethics was issued again in 1993. In 2016, Countryman Press (now a division of Norton) brought out a new edition called The Green Guide to Low-Impact Hiking and Camping.

If you enjoyed this story, you might consider subscribing to our Appalachia Journal.