Choppy Waters: Will Changes to a Northern PA Dam Threaten the Poconos Whitewater Economy?

For more than four decades, Ken Powley has made his living on the Lehigh River. The founder of Whitewater Challengers, a whitewater rafting company in Weatherly, Pa., Powley has guided thousands of visitors over rapids, through a forested gorge and rugged terrain reminiscent of the famed whitewater rivers of the West. For Powley, this water is the lifeblood of his business and critical to the economies and cultural fabric of riverside communities throughout Eastern Pennsylvania.

Because of the Francis E. Walter Dam on the Lehigh River, and routine releases of water from it, eastern Pennsylvania has become a destination for paddlers, with the region’s economy transforming in the process. Tourists spend upwards of $624 million each year on outdoor recreation, according to the Pocono Mountains Visitors Bureau, much of that connected to these waters.

“The number of people that come here for rafting makes it more popular than almost anywhere else in the country,” Powley says. “It’s quiet and serene to be out there. It is an amazing river.”

But the water that feeds the Lehigh—which sits behind the F.E. Walter Dam, owned and operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers—is also part of an interconnected system that has, at times, pitted regional interests against each other.

For much of the 1970s and ’80s, whitewater paddlers and fishers were at odds over how best to manage the dam, and how water was released. Now, paddling enthusiasts see a new threat to their whitewater haven, as New York City, the Army Corps of Engineers, and the Delaware River Basin Commission (DRBC) launch a two-year study of potential future changes to the dam to meet the Big Apple’s own water needs. The study, which began last December and will wrap up in 2022, has restarted and amplified an old debate over how water behind the F.E. Walter Dam is used.

“An elephant has walked into the room,” Powley says. “Whatever differences the boaters and anglers have, it is taking a back seat to New York City and its political influence.”

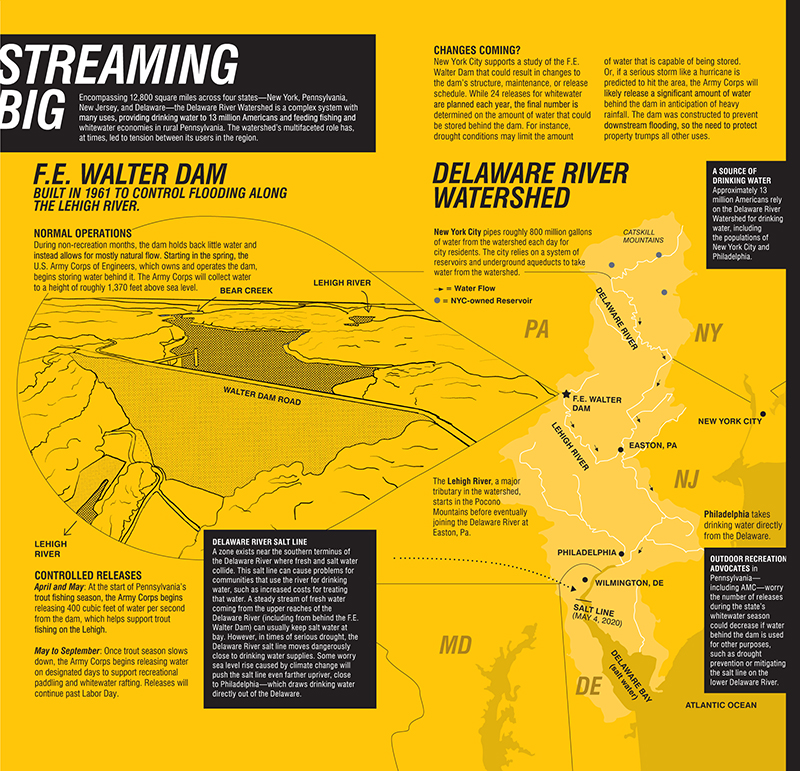

The Lehigh River is a major tributary to the Delaware River. From its headwaters in the Pocono Mountains, the Lehigh empties into the Delaware River at Easton, Pa. From there, fresh water from the river travels past major cities like Trenton, N.J., and Philadelphia, before meeting salt water in the Delaware Bay. This steady stream of fresh water is critical to keeping salt water from reaching farther upriver and contaminating the primary drinking water sources for those communities.

Officials from New York City’s Department of Environmental Protection argue that the water behind F.E. Walter Dam could be better used to keep salt water in the lower Delaware River at bay, preserving more drinking water for the city’s 8.6 million residents. Potential dam changes that New York, along with the Army Corps of Engineers and the DRBC, is researching include raising the dam’s height and altering the controlled water releases.

Outdoors businesses and groups, including the Appalachian Mountain Club, worry that whitewater paddling and guided rafting, with their more than 200,000 participants in the Pocono Mountain region, will take a back seat to the needs of New York City—a conflict reminiscent of those seen in the western United States, where groups have competed for scarce water resources for a century or more.

“This is a contest, and I’m not sure who is going to come out on top,” says Powley, who guided his first rafting trip down the Lehigh River in 1975. “The East Coast is going to find itself in water wars not unlike the epic battles we’ve seen fought in western states, often to the detriment of local communities.”

+++

A COMPLEX SYSTEM

Three human-made reservoirs in the upper Delaware River watershed pull up to 800 million gallons of water a day to meet nearly half of New York City’s water supply. Because New York removes water from the watershed that would otherwise flow downstream, the DRBC—a compact formed in 1961 by four states to manage water within the watershed—requires the city to release a certain amount in order to keep ocean salt water flowing into the lower Delaware River at bay and the communities that rely on the river for drinking water safe.

A zone known as the salt line—where salt and fresh water collide—exists in the lower Delaware River near Wilmington, Del. That line has stayed relatively stable in recent years, but during times of drought, it can move much closer to upstream communities like Philadelphia and Trenton that rely heavily on the Delaware River for drinking water. A creeping salt water line increases the cost to make the water potable and corrodes pipes and equipment. During droughts, water stored in reservoirs is used to offset the creep of salt water into the lower river. Droughts and sea level rise are two of the climate change impacts that DRBC officials are worried could shift the salt line upriver.

“The waters of the basin are interconnected,” says Peter Eschbach, director of external affairs and communications with the DRBC. “What happens with New York City’s drinking water ultimately impacts the people in Philadelphia and Delaware. You can’t look at it from a local watershed standpoint. You have to manage the resources with a more comprehensive look.”

Keeping salt water at bay is a complex dance controlled by the DRBC. Over time, the commission has developed a targeted rate of freshwater flow measured at Trenton, N.J. That flow rate is often augmented through controlled releases from the F.E. Walter Dam, two other dams in Pennsylvania, and at drinking water reservoirs owned by New York City.

“With climate change, they don’t know how much water they will have to save for drinking water and flow objective,” Amy Shallcross, manager of water resource management for the DRBC, says of New York City. “That impacts our ability to control flows in the estuary.”

An agreement on controlled releases was reached between New York City and the DRBC following a devastating drought in 1961 that brought the salt line dangerously close to drinking water supplies, says Paul Rush, deputy commissioner for the Bureau of Water Supply in the New York City Department of Environmental Protection. Since then, the improved science of predicting how much stored water is needed to prevent devastating impacts has led New York City to take a closer look at the F.E. Walter Dam, and how to best manage water in the watershed, Rush says.

“If water releases are done at the right time, you can push back the same amount of salt water with less water, thus improving water storage for drought emergencies,” Rush says. “It seemed to be an idea worth testing further, and the best way for us to do that is to partner on a study.”

The joint study, which is expected to be completed in 2022, will either recommend changes to the dam and its flow management, or conclude that changes are not feasible. Comments will continue to be accepted through the end of this year, and the next public meeting is scheduled for March 2021.

A January public meeting in White Haven, Pa., attracted a standing-room crowd of more than 500 people. Many members of the public who spoke argued that a change in management of the F.E. Walter Dam would only result in New York City being able to preserve more water for its drinking supply by using water behind the dam to offset its responsibility to keep the salt line at bay. That, critics contend, imperils the whitewater industry in the Lehigh Valley.

“We are not going to give up our economy so that New York City can get more drinking water out of the deal,” says Amber Breiner, president of the Carbon County Community Foundation in Pennsylvania, who also spoke publicly at the January meeting. “So many advances have been made in our community because of heritage tourism on the Lehigh River. We don’t want to give up the right to self-determination.”

But New York City officials believe there is a way to still account for all of the water needs in the basin, including whitewater recreation. Increasing the dam’s height, for instance, would allow more water to be stored and eventually released to prevent salt water from reaching the lower Delaware River. City officials argue a taller dam wouldn’t affect the amount of whitewater it can release.

“A gallon of water released from F.E. Walter is more efficient than one released from our dams at pushing back salt water and protecting downstream drinking water,” Rush says. “It makes the entire basin more resilient to drought and climate change.”

+++

RIVER REBORN

The Lehigh River cuts a striking profile as it winds its way through Pennsylvania’s Pocono Plateau, creating a 1,500-foot-deep gorge. Dropping nearly 1,000 feet from its source, the river twists sharply below the F.E. Walter Dam, past launch sites where numerous whitewater visitors start their trips down the river.

The Lehigh River below the F.E. Walter Dam is arguably one of the most accessible bodies of water on the East Coast for whitewater enthusiasts. Much of the land on both sides of the gorge is publicly owned. Four commercial outfitters, all operating under agreements with the state, offer guided rafting trips throughout the summer. At the same time, this stretch between White Haven and Jim Thorpe, Pa., is also used by clubs, including AMC chapters. Over the course of a three-hour trip, paddlers and boaters traverse Class 2 and 3 rapids with hardly any downtime.

One trip down the Lehigh River rapids in a raft, and Jerry McAward was hooked. McAward, who’d come to the valley as a teenager in the late 1970s seeking outdoor adventure, stayed there and eventually opened two outdoor recreation businesses.

“I was struck that this unspoiled river was two hours from Manhattan. Ten percent of the country’s population is two hours away from this river,” McAward says. “The Lehigh has grown into the outdoor recreation memories that people make.”

Paddling first caught on significantly in the 1970s as early pioneers, like Powley, arrived offering guided trips down the Lehigh in the spring. Meanwhile, fishers were in the same waters trying to land trout.

“We had rafts get knifed by fishermen,” Powley recalls. “We were stepping into the river at their key time of year.”

That conflict between paddlers and fishers was resolved in 2005 when the Army Corps agreed to move whitewater releases into the summer season, when there’s less trout fishing pressure. This has resulted in a noticeable surge in the number of paddlers on the river, Powley says. Tourism in the overall Pocono region has grown to 28 million people annually, according to the Pocono Mountain Visitors Bureau, based largely around the abundance of outdoor recreation in the area.

The current flow management plan works and creates outdoor recreation opportunities throughout the Lehigh River, says Mark Zakutanksy, AMC’s director of conservation policy engagement. New York City’s interest in water use behind the dam only threatens to destroy that balance, he says.

“There’s not enough water to go around,” Zakutansky says.

+++

The F.E. Walter Dam, built in 1961 through an act of Congress, is mandated to be used for flood control and public recreation. No matter what the current study recommends, any change to the dam, even in how the water behind it is used, requires Congressional action, says Steve Rochette, a spokesman for the Army Corps’ Philadelphia District.

“It is just a study, a recommendation,” he says. “Our role is to objectively look at things through sound science and engineering.”

AMC joined several other outdoors groups in asserting that any change to the management of the dam, and the water behind it, will likely have a detrimental impact on paddling. In comments jointly submitted in January, AMC and nonprofit American Whitewater assert that any future changes to the dam and its management emerging from the study must result in no net loss of public recreation.

“Over the last 15 years, the economic activity generated by whitewater recreation has surpassed $500 million, twice the value generated by the project for flood control, which is estimated at $265 million,” a portion of the letter reads. “Whitewater rafting, kayaking, canoeing, and fishing are critical to the economy of northeast Pennsylvania.”

The Army Corps balances the interest of commercial rafting companies and trout fishers through its flow management plan. In the spring, water is collected behind the dam to a level of 1,370 feet above sea level. Throughout summer and fall, water is released 24 times to create whitewater rafting opportunities, along with lower-volume flows that flush cold water into the Lehigh River to maintain year-round trout habitats. Without that controlled release of water, the Lehigh would be placid and stagnant by early summer.

Groups, including the Lehigh Cold Water Fisheries Alliance, believe that a new water control tower could significantly extend that cold water zone and make the river an even larger trout fishing destination.

“The F.E. Walter Dam will never go anywhere because it’s mandated for flood control,” said Mike Stanislaw, who serves on the board of Lehigh Coldwater Fishery Alliance. “Now, the question becomes, how do we use the dam to benefit everyone?”

The Army Corps will be weighing these perspectives, competing interests, and potential costs as it finalizes the study of altering dam operations. Another public meeting on the study is scheduled for March 2021, and the Army Corps continues to accept public comments throughout the study on its website.

McAward hopes the Army Corps factors in the economic impact that whitewater rafting has on the local community, including the additional tourist spending at hotels, restaurants, and other local businesses.

To that end, the Carbon County Community Foundation has been working to channel those business interests and push back against any proposals that could harm outdoor recreation in the area. So far, the foundation has collected nearly 2,000 signatures in opposition to changing dam operations, says Breiner, the foundation president. She says the river was once clogged with coal debris and silt; the dam and the water releases have helped wash away that legacy of coal mining and environmental damage.

“The recovery of the river has been a source of pride for our community,” Breiner says. “There is a deep personal connection in our communities and fierce loyalty to our small towns. The river goes through all these places and connects us.”

WHITEWATER ECONOMY IN THE POCONOS

- Visitors spend $624 million a year on outdoor recreation activities—16 percent of all regional tourism dollars.

- Regional recreation spending increased by 5.5 percent

between 2014 and 2018. - Roughly 200,000 people visit the region annually for rafting trips, and 6,000 are employed in the recreation and entertainment sectors.

Sources: Jerry McAward, owner of Lehighton Outdoor Center; Pocono Mountain Visitors Bureau

IF YOU GO

Pennsylvania licenses four whitewater rafting outfitters to operate on the Lehigh River below the F.E. Walter Dam:

Whitewater Challengers

whitewaterchallengers.com | 800-443-8554

Services: Guided trips over Class 2 and 3 whitewater lasting 3 to 4 hours; also offers family-friendly trips with less intense rapids lasting 2 to 3 hours.

Jim Thorpe River Adventures

jtraft.com | 800-424-RAFT

Services: Three different options, including easy rafting; introduction to whitewater; and an intense whitewater trip lasting around 5 hours.

Whitewater Rafting Adventures

adventurerafting.com | 800-876-0285

Services: Three guided options including a 13-mile route with 18 different sets of rapids.

Pocono Whitewater

poconowhitewater.com | 800-944-8392

Services: Three guided options including intense whitewater and family-friendly options; also includes a bike, hike, and raft “Big Day Out” adventure.