What is the EPA? The Agency’s Origins, Importance, and Future

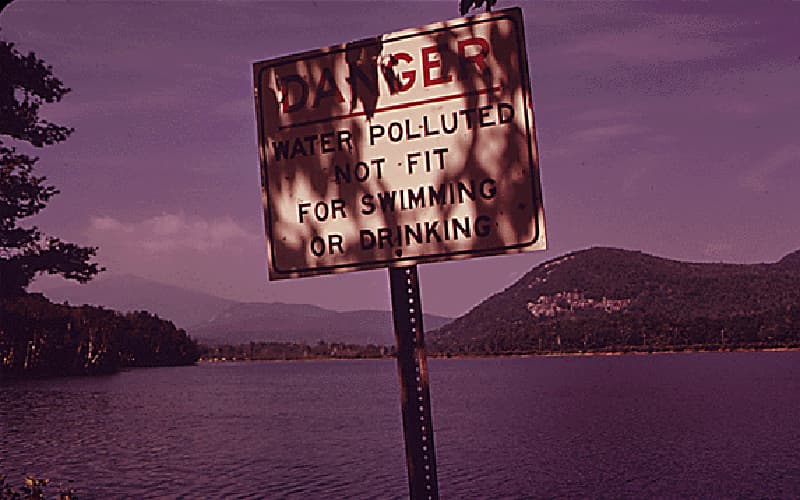

The 1960s were a time of reckoning for humans’ relationship with the planet. The world population ballooned, straining resources. Three centuries of unregulated industrialization and urbanization had poisoned Earth’s air, waters, plants, and wildlife. Rachel Carson’s groundbreaking 1962 book, Silent Spring, awakened the nation and its leaders to the ecological hazards of agricultural pesticides. In communities, colleges, and Congress, calls rang out for a worldwide movement to clean up and protect the environment—decades before we knew to what extent human-caused climate change would threaten our way of life.

If the ’60s was a time to come to grips with the magnitude of the environmental problem, the 1970s began the process of fixing it. The formation of an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was a huge step forward in this regard, consolidating under one federal department the protection of America’s land, water, and air. Now in its 50th year, we see the EPA’s success not only in cleaner rivers and clearer air, but also in the efforts by industry defang and even abolish the agency in response to more stringent environmental regulations. The EPA has overseen one of the largest ecological cleanups in the world’s history, and while its (and AMC’s) work is far from done, the agency is a testament to the role governments must play in safeguarding the natural world.

A Bipartisan Agency

In 1968 and 1969, Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson (D–Wa.) introduced and shepherded a sweeping bill, the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA), that would transform the nation’s environmental laws and create droves of new ones. Jackson envisioned a federal government that would, in the words of the bill he proposed:

“…encourage productive and enjoyable harmony between man and his environment; to promote efforts which will prevent or eliminate damage to the environment and biosphere and stimulate the health and welfare of man; to enrich the understanding of the ecological systems and natural resources important to the Nation; and to establish a Council on Environmental Quality.”

NEPA faced no significant opposition in either the House or the Senate and was signed into law by President Richard M. Nixon on January 1, 1970. This act would, for the first time, assign the federal government the role of environmental protector rather than merely conservator of lands. It was a critical distinction that would lead some to call NEPA the Magna Carta of American environmental legislation.

The Environmental Protection Agency, formed out of the White House Council on Environmental Quality on December 2, 1970, to permanently carry out the mandate of the NEPA. Under the leadership of administrator William Ruckelshaus, the new agency had the power to research pollutants, monitor environmental conditions and establish quantitative baselines, set and enforce standards for air and water quality and for individual pollutants, and support state’s efforts with financial and technical assistance and training. For the first time, Washington, D.C., was the arbiter helping to balance economic progress and environmental stewardship.

Before and After

On December 31, 1970, the Clean Air Act of 1963 (CAA) was amended to grant the EPA power to set and regulate the nation’s air quality standards. New vehicle emissions standards were included in the 1970 amendments (and eventually enacted in 1975), phasing out the use of lead in gasoline. In addition to nearly eliminating the concentration of lead in the air, other quantitative successes from first two decades of the EPA included a 75 percent reduction in particulate emissions as a result of CAA regulation of utility smokestacks and a 50 percent reduction in carbon monoxide emissions from vehicles.

EPA success stories were, in many places, stark. Take the Cuyahoga River, which runs through Cleveland, Ohio. For decades, the factories that lined its banks dumped whatever they wanted—oil, garbage, debris, and any and every chemical you can imagine—right into the Cuyahoga. At least nine times, the Cuyahoga caught on fire because of the pollution on its surface, often burning boats and buildings to the ground. The last time this happened was June 22, 1969, when a spark from nearby train tracks ignited debris on the river, flames spreading across the river and as high as seven stories. Though the river had caught on fire before, this time a recently awakened environmental movement took notice. Some believe the images of a polluted American river literally on fire helped create the political will to ensure it wouldn’t happen again. Seven months after the Cuyahoga River fire, had Nixon signed the National Environmental Protection Act, and 18 months later, the EPA began regulating pollution of America’s land, water, and air.

Today, the industrial channel of the Cuyahoga is still home to a few factories and the tankers that service them, but it’s also enjoyed by boaters and kayakers, luxury condominium owners on its shores, and a thriving aquaculture that many would have thought unbelievable decades ago. Its cleanup is a testament to both local and national resolve and enforcement, ultimately sparking the Clean Water Act of 1972—an EPA-run program protecting the Cuyahoga and all of America’s waterways.

Critics of environmental policy, and the Clean Air Act in particular, point to the costs associated with retrofitting factories and motor vehicles—not to mention the cost of regulating industries. But in 1997, a multi-year EPA report to Congress showed that the economic benefits far outweighed any costs; where the program cost $523 billion over 20 years to implement, its economic value—including improved health, visibility, and crop performance—was as high as $49 trillion.

Clearer Views, Cleaner Air

Hikers today can even see the benefits of the EPA from the summit of Mount Washington. AMC began monitoring visibility in the White Mountain National Forest in 1985 and began measuring levels of airborne particulate material, which causes poor visibility, in 1988. Between 2001 and 2018, visibility on the haziest days has improved by 30 miles in the White Mountains.

The mountain water and air are cleaner, too. After moisture collected on Mount Washington in 1984 showed pH (acidity) levels similar to vinegar, AMC began collecting and monitoring cloud water in the mountains, contributing to the monitoring networks that were documenting acid rain nationally. In 2019, the median cloud and rain water concentrations for sulfate, nitrate, ammonium, and hydrogen ions were considerably lower than the median values collected in earlier decades.

AMC’s monitoring of ozone on the summit of Mount Washington encouraged the New Hampshire Department of Air Resources and EPA to became partners, and the site was then incorporated into EPA’s monitoring network representing the long-range transport of air pollution to our region. According to AMC conservation staff, the reduction in air pollution over time is a credit to EPA-enforced reductions in the emissions that cause ozone pollution. AMC has advocated for programs that reduce emissions like the car tailpipe standards and also has focused on CAA programs that address the transport of pollution because of the role long distance pollution has in impacting mountain wilderness air quality.

“EPA’s role is so crucial in figuring out how to meet the ambitious goals of cleaning our air and water, determining how to reduce emissions as much as possible while still allowing for critical infrastructure like power plants to operate, and requiring and coordinating data to verify that the reductions are working,” says Dr. Sarah Nelson, AMC director of research. “We have seen great success stories in the White Mountains and around the AMC region, based on EPA’s tracking of emissions and their coordination of networks of scientists who study the effects and recovery on our mountain ecosystems.”

Industrial Headwinds

The EPA’s success improving “harmony between man and his environment,” as the NEPA’s original mission stated, is unquestioned. Precisely because of this success in holding industry accountable for its ecological impacts, environmental progress faces near-constant headwinds from powerful energy, manufacturing, automobile, and agricultural lobbies and their political allies. The White House recently has taken direct aim at rolling back several recent and longstanding environmental policies, including the nation’s first greenhouse gas emissions standard for vehicles, passed in 2010; a standard for mercury levels in the air, finalized in 2011; and a 2015 plan to limit greenhouse gas emissions from power plants.

This March alone, EPA issued a supplemental proposal to censor science in its decisions, suspended enforcement of industrial pollution control requirements, and weakened auto emission standards that would have bolstered respiratory health and slowed climate change. In May, EPA proposed changing the Clean Water Act permitting process to allow the federal government to override states’ decisions on specific projects—even when they show a pipeline or a coal terminal would contribute to climate change or worsen air quality.

“Over time, and as part of the public process, we have both supported and opposed EPA in their standard-setting and rule-making,” says Georgia Murray, AMC staff scientist. “As EPA administrators have come and gone, we remain focused on moving towards a cleaner environment and healthier outdoor recreation for all.”