The Only Human for Miles: Deep in the Maine Woods With an AMC Aquatic Researcher

I fumble between my steering wheel and a map along a particularly rough stretch of Ore Mountain about 30 miles Northwest of Milo, Maine, in the geographic center of the state. My eyes scan attentively for the bridge that numerous maps and satellite images have told me lies just ahead. There are many bridges like this one all along these old logging roads, but I’m looking for a particular one today. The bridge I’m seeking has a small stream running underneath it—a stream that will lead me to hidden-away South Pond. I have never seen it before, and a map is my only evidence of it even existing. Although it does not appear to be too far from the main road, South Pond may prove to be a formidable bushwhack.

At last, I come across the bridge I’m seeking and see the stream. I park my vehicle just past the bridge on the shoulder. I can hardly see the flowing water, but I can hear it. Large, ancient boulders impede most of the water in the channel, and the various gaps and cracks amplify the sound of the water flowing underneath—the sound I would follow to remote South Pond. As I shoulder my pack—filled beyond the brim with an inflatable packraft—I feel a sense of excitement and anxiety that comes prior to most of my solo bushwhacks. I make my way along the stream bed feeling both awe and aloneness. The remoteness of this place—20 miles from the nearest house—possesses a duality of both beauty and alienness that I’ve never experienced.

***

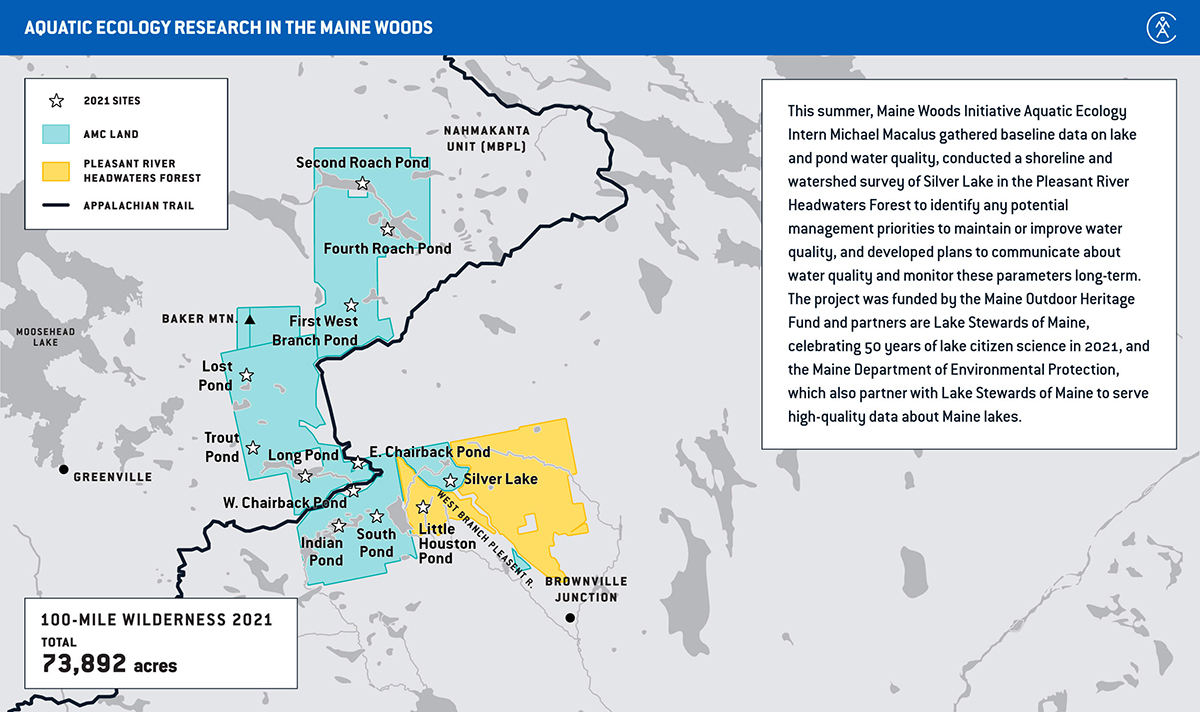

I am an aquatic ecology intern working with AMC’s Maine Woods Initiative, deep in the 100-Mile Wilderness, 150 miles northeast of Portland. This project was funded by the Maine Outdoor Heritage Fund and the AMC Interchapter Paddlers Committee–Waters & Rivers Protection Fund; my task this summer is to assess clarity and collect water samples from the many lakes in the Maine Woods and test and record their clarity and phosphorus levels—attributes that can indicate overall lake health. Clarity and phosphorous sampling are typically the initial tests when looking at an under-researched lake because they provide two important elements. Clarity testing is fairly easy to carry out and can tell us a great deal about a particular aquatic system. Phosphorus is an important nutrient because increases beyond a tipping point can cause major changes to the health of a lake, including algae blooms, so it’s vital that ecologists know how much phosphorus is typical for a study lake or pond. If we are to maintain the healthiest conditions of these lakes, we have to know what “healthy” means in the first place.

Many of the bodies of water in the Maine Woods hold a very unique and special attribute: they have experienced little to no human influence. This is quite rare, especially for the forests of the northeastern United States. The data I am collecting will allow us to begin to understand the “natural” conditions of lakes like these remote lakes, which serve indicators—canaries in the coal mine—for other lakes in Maine, free from significant human impact. What make these data so special is that most lakes globally have been influenced one way or the other by boaters, frequent fishermen, beaches, historical or modern damming, development, and introduced species. All of these impacts influence water samples. Most of the lakes I’m sampling are considered “minimally affected” by human activities in their watersheds. Understanding what a lake looks like without frequent human presence can tell us a great deal about the ecology of aquatic systems and how we can conserve lake environments elsewhere. I believe the most important aspect it helps us understand, however, is the immensity of our impact as a species.

***

Sweat and flies sting at the corner of my eyes. Although I am shaded by a dense tree line, the sun still finds a way to make sure I’m not too comfortable during my bushwhack. After a little more than a mile of hopping along boulders and pushing myself through dense spruces, I see a glorious clearing indicating a large body of water is just up ahead. I dredge through the stream, trying not to trip and fall, and find myself standing at the mouth of one of South Pond’s inlet streams. It’s one of the most scenic bogs I’ve ever seen. Great Blue Herons fly away in annoyance at my entrance, grebes and wood ducks franticly scatter, and a living stew of aquatic insects, amphibians, and small fish dart away from my shadow. This is beauty as pure as I’ve ever seen it, but my luster fades a bit as I observe the shoreline. South Pond is not what I was hoping it would be: The water level is significantly lower than satellite imagery suggested, and the surrounding bog has begun to swallow it up.

I sit down on a nearby boulder in disappointment. The current conditions of South Pond will not be ideal for data collection, and my preparation has proved unuseful. South Pond’s state isn’t even an issue for me to get angry about or inspired by: Small lakes undergo significant changes throughout their lives, and it is a normal and non-concerning ecological reality. Despite my inability to collect samples here, the fact that I had no idea what I would find at South Pond contributes to its uniqueness and value. Its remoteness has served as a shelter from the human world encroaching ever closer. It’s a reminder why AMC’s Maine Woods Initiative—which to date has protected more than 75,000 acres of lands and waters here—matters.

As I sit on that boulder, I take a moment to absorb my surroundings. In this place I thought to be silent, the hum of millions of bumblebees echo in my ears. It is unlike anything I have ever heard. The only thing I can compare it to is a bustling city street full of the sounds of people going about their daily lives. At that moment, it dawns on me that this pond is a mini world with an inconceivable amount of life within its mere three acres. I am a visitor, and the life around me is essentially unbothered at my presence. This world thrives entirely apart from my own existence and would continue after I’ve left. I realize that for all the studying and sampling I am doing this summer, the best way I can help conserve and preserve this system is to value and perceive worlds like this for their own intrinsic rights. Perhaps if more of us recognized natural systems like this as worlds unto their own, we would have more systems like this to enjoy.