Rescue in the White Mountains

In August 2010, AMC Director of Huts and Pinkham James Wrigley received a call that a young hiker was in critical condition after falling hundreds of feet down steep sloping rock. The teen had been hiking on the Huntington Ravine Trail of Mount Washington, one of the most challenging and dangerous trails in the White Mountains. When rescuers reached the hiker, they found he had lacerations across his entire body and multiple broken bones. As they secured their patient to the litter, his condition began to deteriorate. There was no time to wait for additional help. James and the three other responders were forced to embark on a descent that would push them to their physical limits.

There was no time to wait for additional help. James and the three other responders were forced to embark on a descent that would push them to their physical limits.

AMC staff have a long history of participating in search and rescue efforts dating back to the late 1920s. Because they are stationed close to trails in the White Mountain National Forest, they are often the first responders in backcountry emergencies.

“AMC has brought a lot of people to this area over the years, and we should be taking care of the people here, regardless of whether they are associated with us or not,” said James. “A lot of accidents happen because people just don’t check the weather. Sometimes they get summit fever. There’s a drive for people to keep going and finish their itinerary, even when they make a mistake or should turn back.”

At the time of the accident, James had recently begun working full-time as AMC’s Huts Field Supervisor. He had taken a Wilderness First Aid course as part of his job training but had limited experience in the field. When he reached the injured hiker, James was immediately instructed by then-huts manager Eric Peterson to clean the hiker’s wounds and stop the bleeding. “When you show up on the scene, you kind of panic for a second. And then you realize, I have training for this. I know what to do,” he recalled.

“When you show up on the scene, you kind of panic for a second. And then you realize, I have training for this. I know what to do”

Just getting to the teen had been difficult. The AMC White Mountain Guide lists Huntington Ravine as the most dangerous trail in the White Mountains. Its extremely steep and slabby terrain follows sporadically marked blazes. “It’s easy to lose the trail and get into technical climbing terrain very quickly,” James said. Hiking down with the fallen teen proved to be even more taxing.

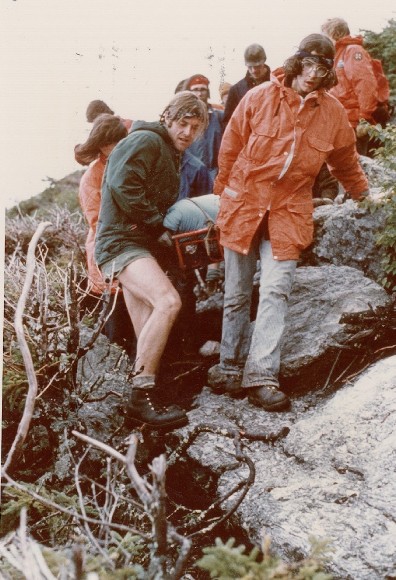

For the job that James and his companions faced, a rescue party of 18-24 would have been ideal. Six rescuers will usually carry a litter to reduce the weight carried by each person and allow for enough mobility. James was one of only four responders to reach the injured hiker. Their patient weighed about 150 pounds, which meant they were each carrying about 40 pounds, one-armed. “We were going through a big boulder field that they call ‘The Fan.’ Usually you stop and switch with a new team every five minutes, but there wasn’t another team so we would stop briefly but tried to push on. You need to keep going. You can’t stop because of the situation,” said James.

“Usually you stop and switch with a new team every five minutes, but there wasn’t another team so we would stop briefly but tried to push on. You need to keep going. You can’t stop because of the situation”

After an incredibly strenuous three quarters of a mile, the group was joined by additional rescuers. Together they helped carry the hiker down the remaining two miles of trail. A helicopter was waiting for them at the trailhead and airlifted their patient to Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center. The rescue team was relieved to hear later that the teen survived with multiple injuries, but no long-term detriments.

Since the 2010 rescue, James has continued to participate in a variety of search and rescue missions. “One of my first fatalities I responded to, I looked through the guy’s phone to find contact information. Seeing the last text that he sent before he died was challenging. Being that connected to someone and carrying his body out stays with me to this day,” James remembered.

“That’s the motivation. You’re going because that’s what you do.”

When asked what motivates him to participate in emotionally and physically demanding rescues, James responded: “It has been a part of my job, but I could have chosen to do it less than I do. Five years ago, there was a winter rescue and I asked my friend to help. As we were setting out in our car, at that moment I realized that we’re just some kids who live in the mountains and just want to help other people who are stuck in the woods in the same way we would want someone to help us. That’s the motivation. You’re going because that’s what you do.”