Emotional Rescue

This story was originally published in the Summer/Fall 2018 issue of Appalachia Journal.

Pam Bales left the firm pavement of the Base Road and stepped onto the snow-covered Jewell Trail to begin her mid-October climb. She planned a six-hour loop hike by herself. She had packed for almost every contingency and intended to walk alone.

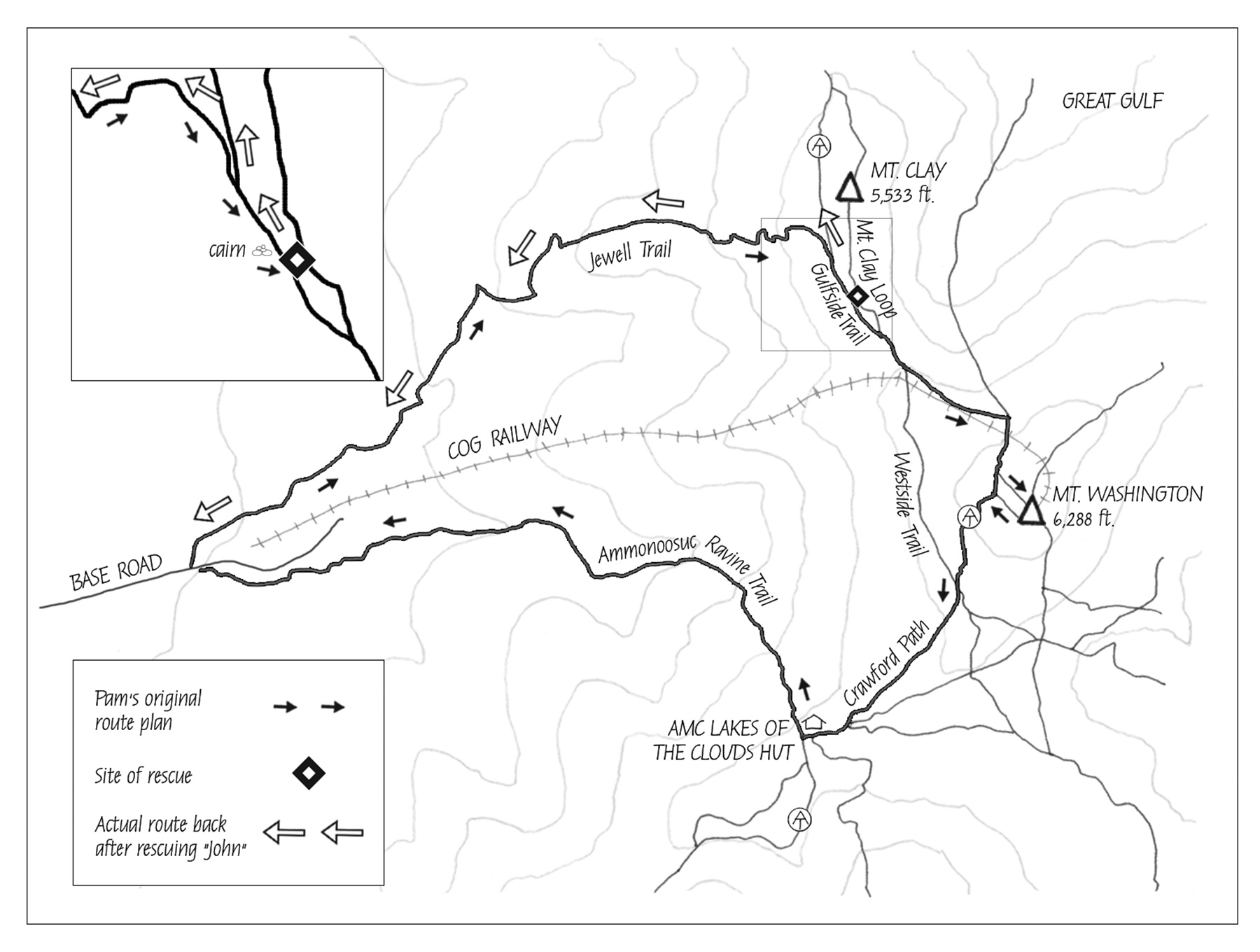

She’d left a piece of paper detailing her itinerary on the dashboard of her Nissan Xterra: start up the Jewell Trail, traverse the ridge south along Gulfside Trail, summit Mount Washington, follow the Crawford Path down to Lakes of the Clouds Hut, descend the Ammonoosuc Ravine Trail, and return to her car before some forecasted bad weather was to arrive. Bales always left her plans in her car, and she left copies with two friends, fellow teammates from the all-volunteer Pemigewasset Valley Search and Rescue Team.

She’d checked the higher summits forecast posted by the Mount Washington Observatory before she left:

In the clouds w/ a slight chance of showers

Highs: upper 20s; Windchills 0–10

Winds: NW 50–70 mph increasing to 60–80 w/ higher gusts

Her contingency plan, if needed, was either to turn around and descend Jewell, or if she was already deep into her planned itinerary, she would forgo Mount Washington’s summit and take Westside Trail to Crawford Path and down Ammonoosuc Ravine Trail.

Bales knew that the forecast promised low clouds with some wind, but based on her experience, her plan of going up Jewell to the summit of Washington and then down the Ammonoosuc Trail was a realistic goal. Her contingency plan, if needed, was either to turn around and descend Jewell, or if she was already deep into her planned itinerary, she would forgo Mount Washington’s summit and take Westside Trail to Crawford Path and down Ammonoosuc Ravine Trail.

She was eager to get out and connect with the mountains and had been waiting for a weather window, however brief, that would allow her to complete the loop. Bales knew the nuances of the Presidentials’ rugged terrain and could hear the weather’s early whispers hinting at an approaching howl. She had packed extra layers of clothing to better regulate her core temperature as conditions changed; the observatory had described conditions on the higher summits as “full-on winter.”

The hike up the lower portion of Jewell was pleasant. Bales felt excited, and her joy increased as she walked up into snowy paths. At 8:30 a.m., still below treeline, she stopped and took a selfie; she was wearing a fleece tank top and hiking pants, and no gloves or hat because the air was mild. The sun shone through the trees and cast a shadow over her smiling face. She had reconnected to the mountains. Thirty minutes later, at 9 a.m., she took another shot of herself, after she’d climbed into colder air and deeper snows. She had donned a quarter-zip fleece top and added gloves. An opaque backdrop had replaced the sunshine, and snow shrouded the hemlock and birch. She still smiled. Above her, thick clouds overloaded with precipitation were dropping below Mount Washington’s summit, where the temperature measured 24 degrees Fahrenheit and the winds blew about 50 mph in fog and blowing snow.

At 10:30 a.m., as Bales breached treeline and the junction of Jewell and Gulfside Trails, the weather was showing its teeth.

At 10:30 a.m., as Bales breached treeline and the junction of Jewell and Gulfside Trails, the weather was showing its teeth. Now fully exposed to the conditions, she added even more layers, including a shell jacket, goggles, and mountaineering mittens to shield herself from the cold winds and dense frozen fog. She made her way alone across the snow-covered ridge toward Mount Washington, and began to think about calling it a day. Bales watched as the clouds above her continued to drop lower, obscuring her vision. She felt confined—and she noticed something. She stared at a single set of footprints in the snow ahead of her. She’d been following faint tracks in the snow all day but hadn’t given them much thought because so many people climb the Jewell Trail. She fixated on the tracks and realized they had been made by a pair of sneakers. She silently scolded the absent hiker who had violated normal safety rules and walked on.

Now, at 11 a.m., Bales was getting cold even though she was moving fast and generating some body heat. She knew she should add even more layers, so she tucked in behind a large cairn on Mount Clay. She put on an extra top under her shell jacket and locked down her face mask and goggle system. Good thing she packed heavy, she thought. And then, hunkered behind the cairn, she decided to abandon her plan to summit Washington. She would implement her bailout plan by continuing to the junction of Gulfside and Westside, turn right onto the Westside Trail and over to the Ammonoosuc Ravine Trail, where she could head down the mountain. Having spent thousands of hours in those beloved mountains, Bales knew when to abort a plan. For her, summiting was just an option, but returning to her SUV was not.

Having spent thousands of hours in those beloved mountains, Bales knew when to abort a plan. For her, summiting was just an option, but returning to her SUV was not.

Strong gusts of wind screamed as they exited the fog at full charge and attacked her back and left side. The cloud cover had transitioned from canopy to the equivalent of quicksand, and the only thing keeping Bales on Gulfside was the sneaker tracks in the snow. How ironic that the unsafe practices of one person should increase the safety of another. At the time, the observatory was noting “ice pellet showers” at the summit, and just north of there, Bales was being assailed by heavy sleet. As she fought with the full conditions on the ridge, her eyes searching for the increased certainty and security of the next cairn, the set of tracks ahead of her made a hard left-hand turn off trail.

Now she felt genuinely alarmed. She was sure the hiker could not navigate in the low visibility and was heading straight toward Great Gulf. Bales stood there, stunned, as she tried to steady the emotional weight of this sudden intersection of tracks. The temperature and clouds were in a race to find their lowest point, she could see just a few feet in front of her, the winds were ramping up, and darkness was mere hours away. If Bales continued to follow the tracks, she’d add risk and time to the itinerary she had already modified to manage both. But she could not let this go. She turned to the left toward Great Gulf and called out, “Hello!” into the frozen fog.

Nothing. She called out again, “Is anybody out there? Do you need help?”

The strong westerly winds carried her voice away. She blew into her rescue whistle. For a fleeting moment she thought someone replied, but it was just the wind playing games with her mind. She stood listening 0.3 mile from the junction of Jewell and Gulfside and about a mile from Westside Trail. She turned and walked cautiously in the direction of a single set of tracks in the snow; her bailout route would have to wait.

She turned and walked cautiously in the direction of a single set of tracks in the snow; her bailout route would have to wait.

As she carved through the dense and frozen fog, Bales continued to blow her rescue whistle. Wind gusts now exceeding 50 mph rocked her center of gravity. Even with her MICROspikes on, she struggled to remain upright on the rime ice–covered rocks. She remembered that the observatory’s forecast had advised hikers to be careful with foot placement that day, as the new snow had yet to firm up between the rocks, so punching through would be an added danger. Bales had also heeded that warning by wearing spikes, but even still, a single misplacement of her boot could put her into serious jeopardy.

She followed the tracks gingerly for 20 to 30 yards. She rounded a slight corner and saw a man sitting motionless, cradled by large rime-covered boulders just off the Clay Loop Trail. He stared in the direction of the Great Gulf, the majesty of which could only be imagined because of the horrendous visibility. She approached him and uttered, “Oh, hello.”

She rounded a slight corner and saw a man sitting motionless, cradled by large rime-covered boulders just off the Clay Loop Trail.

He did not react. He wore tennis sneakers, shorts, a light jacket, and fingerless gloves. He looked soaking wet, and thick frost covered his jacket. His head was bare, and his day pack looked empty. She could tell that he knew she was there. His eyes tracked her slowly and he barely swiveled his head. She knew he could still move because his frozen windbreaker and the patches of frost breaking free of it made crinkling sounds as he shifted.

A switch flipped. She now stopped being a curious and concerned hiker. Her informal search now transitioned to full-on rescue mission. She leaned into her wilderness medical training and tried to get a firmer grip on his level of consciousness. “What is your name?” she asked.

He did not respond.

“Do you know where you are?” Bales questioned.

His skin was pale and waxy, and he had a glazed look on his face. It was obvious that nothing was connecting for him. He was hypothermic and in really big trouble.

Nothing. His skin was pale and waxy, and he had a glazed look on his face. It was obvious that nothing was connecting for him. He was hypothermic and in really big trouble. Winds were blowing steadily at 50 mph, the temperature was 27 degrees Fahrenheit, and the ice pellets continued their relentless assault on Bales and the man who was now her patient.

The thought of having to abandon him in the interest of her own survival was a horrifying prospect, but she’d been trained in search and rescue, and she knew not to put herself at such risk that she would become a patient too. She knew she didn’t have much time. She went right to work. As he sat there propped up against the rocks, semi-reclined and dead weight, she stripped him down to his T-shirt and underwear. Because he wouldn’t talk and she was in such close contact with him, she gave him a name: “John.” She placed adhesive toe warmer packs directly onto his bare feet. She checked him for any sign of injury or trauma. There was none. From her own pack, Bales retrieved a pair of softshell pants, socks, a winter hat, and a jacket. He could not help her because he was so badly impaired by hypothermia. She pulled the warm, dry layers onto his body. Imagine for a moment the extreme difficulty in completing that task in that environment.

Bales next removed a bivouac sac from her pack. She held it firmly so the winds would not snatch it. She slid it under and around his motionless body, entombing him inside. She shook and activated more heat packs that she always brought with her into the mountains, reached into the cocoon, and placed them in his armpits, on his torso, and on each side of his neck. Bales always brought a thermos of hot cocoa and chewable electrolyte cubes. She dropped a few cubes into the cocoa and cradled the back of his head with one hand, gripped the thermos with her other, and poured the warm, sugary drink into his mouth.

All this took an hour before he could move his limbs or say anything. Slurring his words, he said that when he had left Maine that morning it had been 60 degrees outside. He had planned to follow the very same loop as Bales. He had walked that route several times before. He told her that he had lost his way in the poor visibility and just sat down here. Even as he warmed up, he remained lethargic. He was not actively working against her, but he wasn’t trying to help her either.

Even as he warmed up, he remained lethargic. He was not actively working against her, but he wasn’t trying to help her either.

Bales recognized that he would die soon if they didn’t get out of there. She looked her patient squarely in the eyes and said, “John, we have to go now!” Bales left no room for argument. She was going to descend, and he was going with her. The wind roared over and around the boulders behind which they had hunkered down during the 60-minute triage. Bales removed her MICROspikes and affixed them onto John’s sneakers. She braced him as he stood up, shivering, and with a balance of firmness and genuine concern she ordered, “You are going to stay right on my ass, John.” This wasn’t the way she usually spoke to people, but she knew she had to be forceful now. He seemed moments away from being drawn irrevocably to the path of least resistance—stopping and falling asleep. Bales vowed to herself that this was not going to happen on her watch.

She figured that the only viable route out was back the way they’d come, back to the Gulfside Trail, turn right, head back to Jewell Trail, and then descend. That seemed like an eternity, but a half-mile to the top of Jewell was much shorter than the two and a half miles over to Ammo. Bales did not want to head onto Westside Trail or up Mount Washington, where she feared the storm was even more severe. There was something really unsettling about the sound the high winds made as they roared past them and, off in the distance, slammed headfirst into the western slopes of Washington’s shrouded summit cone. She had absolutely no interest in taking them closer to that action.

Visibility was so bad as the pair made their way along the ridge that they crept, seemingly inches at a time. Bales followed the small holes in the snow her trekking poles had made on the way in. She wished she could follow her earlier footprints, but the winds had erased them. Leaning into the headwinds, she began to sing a medley of Elvis songs in an effort to keep John connected to reality—and herself firmly focused. She was moving them slowly from cairn to cairn, trying hard to stay on the trail, and trying even harder not to let John sense her growing concern. He dropped down into the snow. She turned to look and saw that he seemed to be giving up. He curled in a sort of sitting fetal position, hunched down, shoulders dropped forward, and hands on his knees. He told her he was exhausted and had had enough. She should just continue on without him. Bales would have none of it, however, and said, “That’s not an option, John. We still have the toughest part to go—so get up, suck it up, and keep going!” Slowly he stood, and Bales felt an overwhelming sense of relief.

He dropped down into the snow. She turned to look and saw that he seemed to be giving up. He curled in a sort of sitting fetal position, hunched down, shoulders dropped forward, and hands on his knees. He told her he was exhausted and had had enough. She should just continue on without him.

They had traveled just under a half a mile when Bales, and her reluctant companion, arrived back at the junction of Gulfside and the somewhat safer Jewell Trail. It was sometime around 2 p.m. when they started down. The sun would set in three hours. Although the trees would protect them from the wind, it was darker under the canopy. Bales switched on her headlamp as they continued their tortuous descent of the trail’s tricky curves and angles. With only one headlamp between them, Bales would inch her way down a steeper section, then turn to illuminate the trail so he could follow. To help him along she offered continuous encouragement, “Keep going John; you’re doing great,” and sang a dose of songs from the 1960s. Their descent was arduous, and Bales dreaded that he would drop in the snow again and actively resist her efforts to save him.

Finally, just before 6 p.m., after hours of emotional and physical toil, they arrived at the trailhead, exhausted and battered.

Finally, just before 6 p.m., after hours of emotional and physical toil, they arrived at the trailhead, exhausted and battered. Her climb up to the spot where she located John had taken about four hours. Six hours had passed since then.

Bales started her car engine and placed the frozen clothing she had taken off John high on the mountain inside so that the heater could thaw them. She realized he had no extra clothing with him.

“Why don’t you have extra dry clothes and food in your car?” she asked.

“I just borrowed it,” he told her. Several minutes later, he put his now-dry clothes back on and returned the ones Bales had dressed him in up on the ridge.

“Why didn’t you check the weather forecast dressed like that?” she asked him again as she had up on the ridge. He didn’t answer. He just thanked her, got into his car, and drove across the empty lot toward the exit. It was right around that time, at 6:07 p.m., the Mount Washington Observatory clocked its highest wind gust of the day at 88 mph.

“Why didn’t you check the weather forecast dressed like that?” she asked him again as she had up on the ridge. He didn’t answer. He just thanked her, got into his car, and drove across the empty lot toward the exit.

Standing there astonished and alone in the darkness, Bales said to no one, “What the @#$% just happened?”

Bales would not get an answer until a week later, when the president of her rescue group, Allan Clark, received a letter in the mail, and a donation tucked between the folds.

I hope this reaches the right group of rescuers. This is hard to do but must try, part of my therapy. I want to remain anonymous, but I was called John. On Sunday Oct. 17 I went up my favorite trail, Jewell, to end my life. Weather was to be bad. Thought no one else would be there, I was dressed to go quickly. Next thing I knew this lady was talking to me, changing my clothes, talking to me, giving me food, talking to me, making me warmer, and she just kept talking and calling me John and I let her. Finally learned her name was Pam.

On Sunday Oct. 17 I went up my favorite trail, Jewell, to end my life.

Conditions were horrible and I said to leave me and get going, but she wouldn’t. Got me up and had me stay right behind her, still talking. I followed but I did think about running off, she couldn’t see me. But I wanted to only take my life, not anybody else and I think she would’ve tried to find me.

The entire time she treated me with care, compassion, authority, confidence and the impression that I mattered. With all that has been going wrong in in my life, I didn’t matter to me, but I did to Pam. She probably thought I was the stupidest hiker dressed like I was, but I was never put down in any way—chewed out yes—in a kind way. Maybe I wasn’t meant to die yet, I somehow still mattered in life.

With all that has been going wrong in in my life, I didn’t matter to me, but I did to Pam.

I became very embarrassed later on and never really thanked her properly. If she is an example of your organization/professionalism, you must be the best group around. Please accept this small offer of appreciation for her effort to save me way beyond the limits of safety. NO did not seem in her mind.

I am getting help with my mental needs, they will also help me find a job and I have temporary housing. I have a new direction thanks to wonderful people like yourselves. I got your name from her pack patch and bumper sticker.

My deepest thanks,

—John—

Bales was deeply moved by the man’s gesture and his reference to the fact that she made him feel that he mattered. Bales’s selfless act and genuine humility struck a chord elsewhere. Ken Norton, the executive director of the National Alliance of Mental Health–New Hampshire, is a recognized expert on mental health issues who speaks nationally on the topic of suicide. Like Bales, he is also an avid White Mountain hiker. When I shared this story with him, he captured the gravity of Bales’s intervention on the ridge.

“John borrowed a car, got in the car, drove from Maine to Ammonoosuc Ravine, hiked to this spot where he felt like he was going to be past the point of no return, contemplating this the whole way, and along comes this guardian angel out of nowhere who force marches him down the mountain,” he said. “It is important for Pam and others to know that 90 percent of those who attempt suicide don’t go on to die by suicide. John drove away that day and didn’t drive over to the other side of the mountain to go up the other side and finish what he started. He drove home, and a week later, he felt the need to write in an anonymous way to the president of Pemi Search and Rescue to share his immersion back into society and his life. His story represents hope and resilience.”

His story represents hope and resilience

In the eight years since Bales saved John, she has become something of a White Mountain legend. A title she has never sought nor wanted, but certainly one she has earned.

Some people have asked me if I tried to find John. The thought of searching for him felt wrong. As I’ve reflected more on this story and its relation to the issue of mental health, my response to the question about finding John has evolved. I have in fact found John, and he is very close by me. John is my neighbor, he is my good friend, a close colleague, a family member. John could be me.

At some point in our lives, each of us has found ourselves walking with a sense of helplessness along a ridgeline and through a personal storm. Alone, devoid of a sense of emotional warmth and safety, and smothered by the darkness of our emotions, we’ve sought that place just off trail where we hoped to find some way to break free of our struggles and strife. Sadly and tragically, some do follow through. Many are able to quietly self-rescue, and others like John are rescued by others like Pam Bales. The most valuable lesson I’ve learned through this powerful story is to be more mindful of caring for myself and seeking out rescuers when I sometimes find myself on the ridgeline, and to be more like Pam Bales when I sense that those tracks I see ahead in the snow, regardless of who may have made them, appear to be heading deeper into the storm.

At some point in our lives, each of us has found ourselves walking with a sense of helplessness along a ridgeline and through a personal storm.

Ty Gagne is the chief executive officer of Primex, a New Hampshire grouping of local governments for workers’ compensation and liability insurance. He volunteers for Androscoggin Valley Search and Rescue and wrote a book about Kate Matrosova’s death and rescuers’ recovery of her body.

If you enjoyed this story, you might consider subscribing to our Appalachia Journal.